INTRODUCTION

It's a big year for influence. Half the news out of Washington is about who has been trying to buy it, how much they paid, and whether they got their money's worth. There are many lessons to be drawn from that situation. One of the less obvious is that influence is not so easy to come by. Even in Washington, it's not always something you can go out and buy. Just ask the Chinese.

Which brings us to TIME's 25 most influential people, 1997 edition. These are people who have accomplished something subtle and difficult. They have got other people to follow their lead. They don't necessarily have the maximum in raw power; instead, they are people whose styles are imitated, whose ideas are adopted and whose examples are followed. Powerful people twist your arm. Influentials just sway your thinking.

Among this year's 25 are good influences and dubious ones, public personalities and players so private you may not have known they were pulled up to the game board, much less that one of the pieces was you. They include the writer Henry Louis Gates Jr., whose thinking is influential; the chatterbox Rosie O'Donnell, whose cheer is influential; and the rock musician Trent Reznor; whose gloom is influential. (Funny world.) One way or another; these 25 are people to look out for.

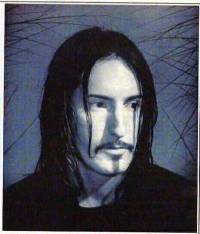

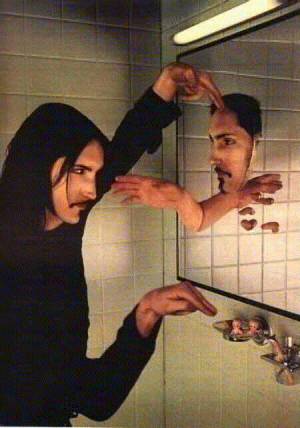

Trent Reznor

Industrial Rocker

Trent Reznor is the anti-Bon Jovi. He is the lord of Industrial, an electronic-music form that with its tape loops and crushing drum machines, harks back to the dissonance of John Cage and sounds like capitalism collapsing. But Reznor, with his vulnerable vocals and accessible lyrics, led an Industrial revolution: he gave the gloomy genre a human heart. It's been said that he wrote the first Industrial love songs.

It is a love that the Marquis de Sade would have found delectable. Reznor's 1994 album The Downward Spiral, for example, was recorded in the house in which Charles Manson'sfollowers murdered Sharon Tate in 1969. But it also features moments of fragility--on the hit song Hurt Reznor sings, "I hurt myself today/ To see if I still feel/ I focus on the pain/ The only thing that's real.." The Downward Spiral sold more than 2 million copies; earlier this year SPIN magazine named Reznor "the most vital artist in music."

Reznor, 31, records as Nine Inch Nails, a one-man studio act, and has a thriving touring career as leader of Nine Inch Nails, a quartet that interprets his computerized compositions before wild fans. He is now nurturing other shock rockers, such as the hard-core horror band Marilyn Manson. Reznor's work is the stuff of nightmares for virtuecrats like William Bennett, but Oliver Stone drafted Reznor to write music for Natural Born Killers, as did David Lynch for his post-noir Lost Highway. Reznor also provides the background music for Goths, a mostly Generation Y subculture of kids who tend to dress in black, vampire-like garb and obsess over death and decay.

Reznor's music is filthy, brutish stuff, oozing with aberrant sex, suicidal melancholy and violent misanthropy. But to the depressed, his music, veering away from the heartless core of Industrial, proffers pop's perpetual message of hope - or therapeutic Schadenfreude: there is worse pain in the world than yours. It is a lesson as old as Robert Johnson's blues. Reznor wields the muscular power of Industrial rock not with frat-boy swagger but with a brooding, self-deprecating intelligence. "I had no expectations of commercial success," he says. "But people 'got it.' That I didn't expect."

The Raygun article can be found here.

Thanks to spydrlyn@fia.net for the Raygun article. Check out her site for some great NiN stuff, including info on tours of New Orleans that stop at Trent's mansion.

Rolling Stone, March 1997

Thanks to Happiness In Slavery for the Rolling Stone pics.

"Death to Hootie!"

Trent Reznor Makes a Case for Danger

-by Mikal Gilmore

Rolling Stone, Issue 755

March 6, 1997

Transcribed by Andy Ryder

Some of the most wondrous moments in David Lynch's Lost Highway owe significantly to the aural genius of Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor. His thick, ambient drones - during the film's mysterious video sequences - give the fated house where the film's two main characters, Fred and Renee, live a life all its own; it's as if the walls were breathing and murmuring, or trying to whisper horrid secrets. In his own way, Reznor has created a tense and powerful soundscape here that is inventive (and likely to be as style defining) as Bernard Herrmann's orchestration for the famous shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho.

Like Lynch, Reznor is one of the artists who is helping to change popular culture's mainstream sensibility. His1994 album, The Downward Spiral, is among the most radical sound assemblies ever to become a multi-million seller, and also one of the most ingenious: It mixes violent textures with lovely melodies, all to frame a harrowing, deeply affecting story of one man's descent into his own abject soul. The effort made Reznor a major star - and a busy one. In the years since, he has toured with Nine Inch Nails, supported David Bowie on another big tour, produced the startling soundtrack for Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killersand also helped produce three CD's for shock-rock fave Marilyn Manson, including Anti-Christ Superstar. Reznor also became a target for cultural moralists William Bennett and C. DeLores Tucker, who expressed outrage at what they viewed as his music's assault on decency. What Bennett and Tucker fail to comprehend is that there is more than one mainstream in America. There's a mainstream in which people acknowledge and cope with pain and fear and anger. It's not a small one; if it were, there wouldn't be so much disturbing or so-called dangerous art that is also so popular. Reznor is a star not just because he makes great sounds or looks sexy; he's also a star becasue his audience likes and needs to hear what he has to say.

His new songs on the Lost Highway soundtrack (which also includes new music by the Smashing Pumpkins, Marilyn Manson, Lou Reed and David Bowie, among others) are the only things we'll be hearing from Reznor for a while. He's working simultaneously on two new records, but he isn't willing to say when they'll be released. I interviewed him twice - once in his Los Angeles hotel room and a second time during a late-night phone conversation. I found him to be a gentle-mannered, soft-spoken and steadily thoughtful man who isn't afraid to say strong things.

_How did you come to work with David Lynch?_

He was looking for somebody to provide some of the sound for Lost Highway, and a friend suggested he give me a call. I hadn't seen the film, but I'm a huge David Lynch fan - we used to hold up Nine Inch Nails shows just so we could watch the latest Twin Peaks. So we set up a weekend for him to come to my place in New Orleans. At first it was like the most high-pressure situation ever. It was literally one minute, "Hi, I'm David Lynch," and he's cooler than I ever imagined he would be. Three minutes later, he's saying: "Well, let's go in the studio and get started." Then he'd describe a scene and say, "Here's what I want. Now, there's a police car chasing Fred down the highway, and I want you to picture this: There's a box, OK? And in this box, there's snakes coming out; snakes whizzing past your face. So, what I want is the sound of that - the snakes whizzing out of the box - but it's got to be like impending doom." And he hadn't brought any footage with him. He says, "OK, OK, go ahead. Give me that sound."

He wasn't doing it to intimidate me. At the same time, I had to tell him, "David, I'm not a film-effects guy, I don't have ad clients, and I'm not used to being in this environment. I don't work that way, so respect that and understand that I just need a few moments to be alone, so that I know that when I suck, no one is knowing that I'm sucking, and then I'll give you the good stuff." I'm thinking, "Boy, he must really think I suck now." But by the end it went cool. And then he turned over all the music that was in the film and asked me to make a CD out of it. So I've done my best to make the CD a fair representation of the film, because this isn't Mortal Kombat, you know. This is David's movie. To the person that hates pop music who buys this David Lynch soundtrack, they will get what they want out of it. At the same time, I want it to have some degree of accessibility for the 13-, 14-year-old kid who buys it because I have a new song on it; or for the Smashing Pumpkins fan who buys it for that. Anyway, I think the whole thing flows, and that's my main contribution to the project.

_What was your estimation of the film?_

When I saw the finished one, I thought, "Fuck, this is fantastic." It's abstract and bizarre, but it also has enough payoff. But there is that one weird night in the movie [when Fred transforms into Pete Dayton]. I wanted to know what the fuck happened that night.

_There's no really easy closure in the movie. It's more like a Mobius-strip story than a beginning-to-end narrative. That may prove difficult for some viewers . . ._

But that's another reason to praise [Lynch], in the sense that he's not really catering to them. When I saw Blue Velvet, I walked out of the theater changed and very shaken. I talked to someone later, and they said, "Didn't you think that was funny?" I didn't think it was funny. I was terrified, because, when I saw it, I realized I would have done the same thing as Kyle MacLachlan's character. I would've tried to sneak in, I would've felt for her - I would've done it all.

I also remember the Twin Peaks episode where Leland bashes Maddie's head against the wall, and then he's driving the car with the body in the back. I thought, "This is the scariest, most violent thing I've ever seen on television, ever. Fuckin'-A, someone got away with it." I could also see why people had a problem with it. It wasn't, you know, Fresh Prince of Bel Air.

_I think that with that series, he was tapping into a conciousness of America that America wasn't quite ready to accept from its mass entertainment_.

That reminds me of something David said to me one night. We drove past some billboard of some soon-to-be-playing movie. And he says, "You know, I kind of envy, in a way, someone like Steven Spielberg, who I think really does what they believe in 100 percent, and it just happens to jibe with the conciousness of America and its billion dollar-making movies. I don't think he's catering to the market so much as he's doing what he really believes in. I do what I believe in, which is all I can do, and it gets a slice of whatever." It struck me as an interesting way to look at things. I could see where, as a director, you could be bitter about the guys who have that success, but that isn't him. It impressed me, that sincerity, almost a naivete.

Sometimes in my music, I'll try things, and I'll think, "No one's going to like this, but it's not fucking Bush." I'm not claiming it's the weirdest avant-garde contemporary piece ever, but hopefully it challenges you. Either you don't like it, or you think, "Fuck, that's cool - that makes me realize how shitty the stuff is that I've been listening to." I'm stretching it a bit here, patting myself on the back.

_Years ago, Lynch told "Rolling Stone" that part of what he was trying to do with his films was "to make art popular." Does that in any way describe what you are trying to do with your music?_

Well, it sounds pretentious to say that, but, yeah, I do look at it as art, not just as selling records or making a commercial product. I'd like to open people's eyes up to something a little bit different than the mainstream crap that's out there. I think I took a lot of the things I liked and kind of recycled and hopefully added something to them - maybe that hook that they didn't have before - and maybe that might reel in a listener who wasn't as in tune with that sort of sound. Maybe it opens their eyes to a new thing. That's the aspiration, anyway.

_But because your work does well on the charts, doesn't that also make your music, in a sense, mainstream?_

If you'd asked me years ago, when I started, I'd have said, "No, I'm not mainstream." But that's a blanket of protection you wear to avoid saying something that could be perceived negatively. Yeah, I think my music is mainstream. You can't sell that many records and still think that you're in the underground. I'm not saying you can't have that underground or alternative element to it, but the underground has infiltrated, to some degree, into the mainstream. But the reason I sleep well at night is because I know I didn't try to cater to the mainstream. Before The Downward Spiral came out, I said to the label, "Look - sorry, but I don't think there's a fucking single in here. I don't think it's going to sell for shit, but I had to make this record, because it's what I'm about right now; I believe in it 100 percent. I'm sorry, though, there's not something to justify the money you gave me to make it." Then "Closer" takes off, and the fucking record sells 2 or 3 million copies. It surprised me because - not to sound lofty, but I didn't think people would get it, you know?

_Why is that?_

Well, I made the first song on the record, "Mr. Self Destruct," sound like I wanted it to be: the shittiest sounding thing that, by the end, just deteriorates into noise. It is not fucking Michael Jackson. Then I followed it with a light, swinging jazz song - just the exact opposite of what you'd expect. And then with "Closer." . . . I wrote that song, and I was afraid to put it on the record. I thought I could make a whole album of noise with me screaming, and I'd be safe, at least with the people who liked Pretty Hate Machine. But instead, "Closer" is a song with a simple disco beat and a Prince kind of harmony vocal line. That, I thought, would open me up to a lot more criticism from the safe company of alternative people I'm supposed to be catering to. Then, when The Downward Spiral took off, I thought, "Fuck, this is what I want to do." It should be like that, you know.

The new stuff I'm working on is even more disparate than The Downward Spiral. I'm not afraid of trying things out. This next record: It will either be huge or a career stopper. It won't be safe, that's all.

_You alluded to the purism of the alternative audience, which can sometimes prove pretty maddening. It's as if once you've made music that reaches a truly large audience, both you and your work become suspect._

I went through a phase where I thought we [Nine Inch Nails] were the cool thing that only a few people or critics knew about. And then our records started infiltrating suburban malls. And then little kid sisters started wearing Nine Inch Nails shirts. And then, suddenly, it's not as cool as it was before, even though it's the same music. And I had this knee-jerk reaction: "Fuck you, and now I'm more pissed off, so I'll make something even more unlistenable." But I wasn't being true to myself then. I was catering to an audience that I was trying to re-prove my credibility to. And some of those people are full of shit in the first place.

Let me tell you about something that really helped me out: I saw U2 for the first time, on their Zoo TV Tour. I was backstage with Marilyn Manson, sitting in a room, and Bono comes in. I'd never met him, but we knew of each other through Flood, the producer who worked on both of our records. Bono sat down and talked with me for an hour, and we had this kind of drunken mind meld. I said: "I'll tell you what I'm going through now. We went from being underground-elite darlings to the point where we're getting shit on by those same people because now we sell records. And I know you guys have gone through the same thing." Bono says: "Fuck those people. That's like saying, 'You're cool enough to listen to my music, but you - you grew up in Wisconsin; you're not cool enough to listen to it.' That's a kind of fascism." He goes, "You do what you believe you have to do. That's what we've always done. You believe in yourself and don't worry about the people who don't like it because it's not the right fashion statement that they're trying to adhere to."

Now U2's not my favorite band, but I do respect them, and in the same way I respect Bowie: They change without fear of change. I left that night thinking, "He's right. Why am I concerned about some snotty-nosed college magazine that thinks I'm not cool because people liked the record and bought it?" After that, I got over that whole thing.

_Well, there's a flip side to that. Because a lot of people like your music and seem to identify with what you're saying, some writers have said that - just like Kurt Cobain a few years ago or Bob Dylan a generation ago - you are now speaking to and for a certain generation and its sensibility or experience. Are you comfortable with that description?_

It's an unwelcome statement because I don't consider myself that at all. I never have. I think that maybe what I'm saying, people of that generation picked up on and related to, but by no means do I think that. . . . Look, I just sat in my bedroom and wrote how I felt, why I was upset about things, filled up a piece of paper and sang it, and then people related to it. That's as far as it goes. There isn't anything lofty about it.

_But you have also been criticized for being a bad influence on your audience. Your song "Big Man With a Gun" was cited by William Bennet and C. DeLores Tucker as being dangerous because of its violent imagery. Your music and that of Tupac Shakur and the Death Row gangsta-rap artists were a large part of why Bennett and Tucker demanded that Time Warner disavow its relationship with Interscope Records._

They don't have any idea what they're talking about. They called Nine Inch Nails a rap band. I think my music's more disturbing than Tupac's - or at least I thought some of the themes of The Downward Spiral were more disturbing on a deeper level - you know, issues about suicide and hating yourself and God and people and everything else. But I know that's not why they singled me out. They singled me out because I said fuck in a song, and said, "I got a big gun and a big dick."

_Do you ever worry that some music could have a damaging influence on an audience? I remember, for example, Lou Reed once telling me that he'd stopped performing "Heroin" for a time because too many people told him that song had inspired them to shoot junk._

That song's a piece of art, though. The first and only time I ever tried heroin, I listened to that song. I was in a big Lou Reed phase, and heroin seemed like this whole glamorous . . . thing. Then I realized, "Hey, this is shitty." It wasn't really the song - it was my own decision and my own stupidity. You could say that song is dangerous, but it should be. If nothing else, it brings the subject to light, you know.

I did a song on Downward Spiral where I'm talking about killing myself. I dreamed it, and I thought it, and it was like, "Oh, God, I'm going to do this." So I wrote it into a poem, and I found it tied in with the theory of the record: that at the worst state the character goes into, suicide might be an option. But I think by just saying it and bringing it to light, maybe it helps. I've been so depressed about things, and then I'll hear a song, and I'll think, "Fuck, I can relate to that. Someone else feels that way." In its own way it becomes enlightening, and I feel release. When I'm onstage singing - screaming this primal scream - I look at the audience, and everyone else is screaming the lyrics back at me. Even though what I'm saying appears negative, the release of it becomes a positive experience, I think, and provides some catharsis to other people.

_In a way, that brings us back to the subject of the mainstream. Some of these same moralist critics say that what's bad about music like yours is that it assaults or offends mainstream values._

When I was growing up, rock & roll helped give me my sense of identity, but I had to search for it. I remember I loved the Clash, but I was an outcast because you were supposed to like Journey. Before that, I loved Kiss. The thing these bands gave me was invaluable - that whole spirit of rebellion. Rock & roll should be about rebellion. Rock & roll should be about rebellion. It should piss your parents off, and it should offer some element of taboo. It should be dangerous, you know? But I'm not sure it really is dangerous anymore. Now, thanks to MTV and radio, rock & roll gets pumped into your house every second of every day. Being a rock & roll star has become as legitimate a career option as being an astronaut or a policeman or a fireman. That's why I applaud - even helped create - bands like Marilyn Manson. The shock-rock value. I think it's necessary. Death to Hootie and the Blowfish, you know? It's safe. It's legitimate.

Look at Marilyn Manson: They have no qualms about taking that whole thing on. The scene needs that, you know. It doesn't need another Pearl Jam-rip-off band. It doesn't need the politically correct R.E.M.s telling us, "We don't eat meat." Fuck you to all that. We need someone who wants to say, "You know what? I jack off 10 times a night, and I fuck groupies." It's not considered safe to say that now, but rock shouldn't be safe. I'm not saying I adhere whole-heartedly to that in my own lifestyle, but I think that's the aesthetic we need right now. There needs to be some element of anarchy or something that dares to be different.

_But a lot of people would say that art - whether it be music, film, or any other form - has an obligation to improve the world. Do you think art has any obligations?_

I do in the sense that I think it might help somebody understand themselves better. It's like what we were talking about before. I write a song about killing myself. You hear it, and you go, "I'm not the only person who ever felt that way." You feel safer in knowing you're not the only person who ever thought that. And I think: "Mission accomplished." To me, that's the way art communicates to people, that's how it helps.

_What about the art that addresses people who might want to kill somebody other than themselves?_

There's a part of me that is intrigued by that. For example, I loved the Hannibal Lecter character in The Silence of the Lambs. The last person I want to see get hurt in that story is him. And I think, "Why do I look at him as a hero figure?" Because you respect him. Because he represents everything you wish you could be in a lawless, moralless society. I allow myself to think, "Yeah, if I could kill people without reprimand, maybe I would, you know?" I hate myself for thinking that, but there's an appeal to the idea, because it is a true freedom. Is it wrong? Yeah. But is there an appeal to that? Yeah. It's the ultimate taboo.

My awakening about all that stuff came from meeting Sharon Tate's sister. While I was working on Downward Spiral, I was living in the house where Sharon Tate was killed. Then one day I met her sister. It was a random thing, just a brief encounter. And she said: "Are you exploiting my sister's death by living in her house?" For the first time the whole thing kind of slapped me in the face. I said, "No, it's just sort of my own interest in American folklore. I'm in this place where a weird part of history occurred." I guess it never really struck me before, but it did then. She lost her sister from a senseless, ignorant situation that I don't want to support. When she was talking to me, I realized for the first time, "What if it was my sister?" I thought, "Fuck Charlie Manson." I don't want to be looked at as a guy who supports serial-killer bullshit.

I went home and cried that night. It made me see there's another side to things, you know? It's one thing to go around with your dick swinging in the wind, acting like it doesn't matter. But when you understand the repercussions that are felt . . . that's what sobered me up: realizing that what balances out the appeal of the lawlessness and the lack of morality and the whole thing is the other end of it, the victims who don't deserve that.

_You've talked a lot in the past - and on "Downward Spiral" - about self-loathing. Would you say that you now like yourself better than you did before?_

I've got more thanks and praise and more money than before. But from a self-esteem perspective, I've liked myself more. . . . I've lost friends. I've lost band members. I've lost a sense of self-worth in a way. And while I always wished I'd get to this place of success, once you get it, it's not that great. I'm not bitching about it. I mean, it is great in a million ways, but it's not self-affirming on every level, and you wish it was. I don't go to sleep thinking, "I'm Kevin Costner," you know, "I've done it!"

And the bigger you get in the rock arena, the more people want to fuck with you, to tear you down and criticize you. For example, you write a song you think is dangerous to write because it says something that you're embarassed to say. But because it's embarassing, because it's extreme in its nature, then you've got everyone saying, "He doesn't mean it. He's just trying to cash in." You find yourself initially saying, "Yes, I did. I meant it. I am that bummed out."

I would only hope that maybe, in a world of insincere, bullshit, pop-music crap, this music might make a difference. And that's why I do it: I think it does. But at the same time, think how much easier it would be to be a bland rock band that doesn't mean anything and just make money.

_What will the new music be like?_

There will be two records that will probably come out around the same time. One will be with people I had with me in the live band. We're playing and writing together in a band called Tapeworm. That one will be a little bit more like what you think industrial music is like now. The new Nine Inch Nails will be more like a funk hip-hop record. It will piss a lot of people off, and it's going to change the world at the same time, I hope. That's all I can aspire to. That and staying 10 steps ahead of Billy Corgan.

SPINOnline, February 1997

This interview is from SPINOnline (on america online).

Click here to listen to a short .wav sound of Trent talking about his music from this interview.

SPIN interview:

TRENT REZNOR:

The Devil Said to Me

-by Jeff Rotter

------

SPIN: Hello, hello, hello... Where am I calling?

Trent Reznor:

I'm in L.A. right now.SPIN: What's going on?

TR: We just finished shooting the video for a new song off the David Lynch soundtrack. And some miscellaneous publicity-type crap that you have to do. It's a necessary evil.

SPIN: Our main topic today is your protege, Marilyn Manson. What is your relationship to Manson and his band?

TR: I've been friends with Brian for quite a long time, and I think he looked at me as a sounding board with an honest opinion. Not that it's always a great opinion, but at least it's no-bullshit. If something's bad, I'll say I think this is bad. On the Portrait album, they worked with a different producer, and they'd done this whole series of mixes. After it was done, he played it for me, and I listened and listened overnight. I went to him the next day and said, "I know you don't want to hear this, but I'm saying this as a fan, I don't think this is as good as it could be. Whatever was raw and good about the demos got lost in the polish." He thought about it and said, "You're right. I've been trying to convince myself that it's good, and it's not."

SPIN: So, you took on the reconstruction of Portrait. Antichrist Superstar, which you coproduced from the beginning, is a much more mature record and a riskier production job.

TR: When he started on this record, Brian considered a lot of older producers who did more bombastic, over-the-top production. But he came back to me and said, "Would you like to do this with Dave Ogilvie?" (Dave and I had been working on some live David Bowie mixes.) So, we took the project on.

SPIN: How do you define your role as producer?

TR: Brian--er,Manson--has a pretty good idea of what he wants, and he's a really hard worker. And he's learned a lot from when I first met him. He's gone from not knowing how to get the sound he has in his head to pretty much having a grip on how the studio works. My role in this record was to create an environment where I kept the flow going. There were some internal problems with getting rid of the guitar player. There was such an animosity between the camps that, on one hand, I was playing counselor, using a lot of stuff I learned from working with (U2 producer) Flood. When I got a short fuse in the studio working on my own stuff, he'd say, "Go read a book. Go ride your bike." When you get stuck, know that you're stuck, don't try to break the wall down. And also, I was the organizer. When we started the whole thing, I said, from hearing the demos, let's get over the dread of saying "concept record." All these songs seem to fit into a story. I layed out what I thought the order would be before we recorded one note of music.

SPIN: Just based on the demos?

TR: Yeah. Because the band broke down into Twiggy, Pogo, and Manson doing everything, they were more open to trying different things. There were times when we were all sitting down with guitars, trying stuff together. What I wanted to do was show that the band had some scope. It wasn't all just guitar-bass-drums rock. I thought one song should sound like it was recorded on a Walkman and the next would have a Queen level of overprod- uction. They said, "But we want it to be tough." The thing I learned with my own music is if you make a whole album of 200 b.p.m. songs, after about three minutes it's not that scary anymore. You need to break it up and develop some tension. I wanted to embrace production on this record rather than strip it down.

SPIN: Yeah, it's interesting that you took them on because they suffered from overproduction, but Antichrist is clearly a producer's record. Was there resistance to your suggestion that this be a concept record?

TR: Well, I said, "We don't have to tell anyone that that's what we thought at this point." They were always open. It was the first time that I ever had that level of interaction as a producer. I was in there from the start. It got me away from Nine Inch Nails for a while, too, which is something I wanted.

SPIN: Do you plan to tour together again?

TR: We'll be on opposite tour schedules for a while. Plus, I don't think it would be beneficial for them to open up for us at this point, or vice-versa. They're big boys now.

SPIN: They seem to finally be working to their potential on this album. You must be very proud.

TR: Well, it's just nice to hear somebody do something different. I mean, Bush? Christ. Enough already.

SPIN: How did you handle the band differently on this record?

TR: Well, it's a different band. I think there are some good songs on Portrait, but I'm not particularly proud of the record as a whole. I think the main difference in the band from then to now is that Daisy, the old guitar player, actively wrote the music. On this record, Twiggy, who joined after Portrait, and Brian worked on most of the stuff together.

SPIN: What was the source of Daisy and Manson's falling out?

TR: Things had deteriorated on tour. Brian didn't respect him, he didn't respect Brian. It got into that kind of vibe. If you put a bunch of guys together in a tin can and send them down the road for two years, these weird character distortions take place.

SPIN: There are a lot of interesting rumors about how you kept the band entertained during Portrait: male strippers, etc.

TR: I think "rumors" is the key. I read some things like, I mix with a Quiet Riot helmet on, shit like that.

SPIN: That's not true!?!

TR: I won't shatter anybody's illusions. I can only imagine what some people who take everything that they read literally will think.

SPIN: Is there any truth to the stories we read about the atmosphere in the studio during Antichrist?

TR: A lot of ridiculous stuff went down. The first rule was we all had to grow mustaches. My beard comes in this horrible color of red for some reason. When we'd grown them, we all laughed, except for Twiggy. He's too fucking vain. There was a show coming he wanted to go to so he shaved. But we got to the point where we looked so stupid. You'd run into somebody and forget you had it on. Then you'd try to explain: "This is a joke." Manson and I joked about getting spotted at Tower Records, and instantly our records get returned. You know, "Those guys aren't cool anymore." I have some great photos of Manson in his Journey t-shirt. Pretty classic.

SPIN: What's on your agenda now?

TR: I'm about to go to Big Sur for a couple of months and sit with the piano and write my new record. That'll take me out of the loop for quite some time. I'm also working on a new band called Tapeworm, which is the other guys in my band, with them more active in the music-writing department. It's fun. Even though it's the same camp of people, we've changed people's roles.

SPIN: Is the music different?

TR: It doesn't sound like Nine Inch Nails to me, other than my voice. It's a bit more obvious. I have such high standards for Nine Inch Nails. Every- thing has to be a big leap ahead on every level. I don't know if that sounds incredibly pretentious. I have songs that aren't right for what I think the next Nine Inch Nails thing is going to be, and they fit with Tapeworm. Here the pressure is off, so the songs get a chance to get better. Sometimes I put the weight of the world on my shoulders, and I psyche myself out. It's a little mental trick I have.

SPIN: Do you generally write with the piano?

TR: No, but I'm trying to make myself this time. I think the only song I ever wrote sitting at a piano was "Hurt." And it's one of my better melodic structures. I really like Tom Petty. He writes a good song with three simple chords, but there's always something about it that's cool. I app- reciate a well-written song, and I aspire to become a better songwriter.

SPIN: You are known as a "studio wizard," aren't you? You rarely ever get called a great singer/songwriter. Do you think stripping away the studio technology will improve your songcraft?

TR: Yeah. The easy part is getting it to sound cool, dressing it up. Plus, I want to get back to playing piano. I want to get back to being good at something. I'm average at a lot of things.

SPIN Magazine, April 1997

Thanks to Happiness In Slavery for the Spin pics.

The Spin 40: The most vital artists in music today

NINE INCH NAILS

SPIN Magazine

April 97

Photographs by Andrea Giacobbe.

What's it take to be named the Most Vital Artist in Music Today? A singular vision, scores of imitators, and a willingness to trash the competition. As Nell Strauss learns, Trent Reznor fits the bill perfectly.

Eight years ago, Trent Reznor seemed like a throwback, beating the dead horse of industrial rock. Today, he seems like a visionary, the first rock star to make synthesizers cool for teenage headbangers, paving the way to popularity not just for countless knock-off industrial acts but also, to some degree, for the hyper-trendy beats of techno and electronica. Unlike many musicians, Reznor is savagely aware of his place in the current strata of pop stars. He constantly compares himself to other musicians, saying that he "

can't write a thousand songs like Billy Corgan," that he's "not as careerist as [Marilyn Manson]," that he "can't sing about [his] big dick like David Lee Roth." It's for this reason, in large part these intense feelings of self-consciousness and competition that the most vital artist in music today has completed only one new song in the past three years. While cleaning off a place on the couch at Reznor's cliff side house in Big Sur, where he's holed up writing the follow up to 1994's The Downward Spiral, I spot an envelope. Scrawled in black pen are the words NEW SONGS. I don't open it. I do notice, however, that it's very thin.SPIN: is it fair to say that you suffer from writer's block?

Trent Reznor:

I'm afraid to really push myself and write because I'mafraid of failure. When I was doing The Downward Spiral, I was kind of freaked out, and Rick Rubin, who's doing the new record with me, was trying to talk to me. And I just wanted to kill myself. I hated music. I was like, "I just want to get back on the road because I hate sitting in a room trying to, trying to"—how do you say this?—"just scraping my fucking soul." Exploring areas of your brain that you don't want to go to, that's painful. You write something down and you go, "Fuck, I can't say that. I don't want people to know that." It's so naked and honest that you're scared to let it out. You're giving a part of your soul away, exposing part of yourself. I avoid that. I hate that feeling of sending a tape out to someone: "Here's my new song. I just cut my soul open. Check it out. Criticize it."

Let me ask you then: Why do you think SPIN chose you as the most vital artist in music?

I don't know. I've no idea. I was pretty shocked when I was told, "Hey, you're number one." I was like, "Is this good?" Because I can already read the letters the next month saying, "Fuck that, man. why didn't you choose so-and-so."

It's nice, though, to have some kind of mainstream-media appreciation. I thought we'd always skirted super-attention. There are a hundred books on Courtney Love in Waldenbooks and there's none on us. So it's flattering. But, you know, I'm just a footnote in rock history, the guy that had mud on at Woodstock. "Where Are They Now: The Nineties."

Do you ever wonder, "How am I going to make sure I matter in the next decade?"

Jimmy Ovine of Interscope Records, who I respect a lot, said to me at one point, "I'm president of Interscope and not a producer anymore because I see guys like you and Dre come along, and I can't compete on that level." When you think about the rock world, there's a window of time where what you do has pertinence and meaning. I hope ten years from now I'm making soundtracks or producing or something. I don't want to be putting mud all over myself at the Sands in Las Vegas.

I'd love to think someday that I made a difference, I changed something, I shifted the axis somewhat. But all I can do is try to make the best music I can. Not go into it thinking, "I'm going to change shit." It becomes calculated if you cater to the idea of shifting things. I think we have in a subtle way, but, um, yeah, I'd love to be remembered. [Sarcastically] Elvis, Lennon, Reznor.

Do you think that you helped pave the way for the mainstream acceptance of techno and electronica?

Maybe. It starts sounding real egotistical if I take any stance on that. But to answer your question, I think we definitely took a certain element of harder-edged electronic music to the shopping mall. You might say that my success was to take industrial music and add a melody to it, add an element of pop to it. It connected with people in a way that we didn't anticipate.

How about these sort of one-hit-wonder industrial bands like Stabbing Westward and Gravity Kills. Do you feel responsible for them?

Look at it in terms of the music-industry follow-the-leader approach: "Okay, Nirvana's big, let's sign every band that sounds like them " I'm sure after Nine Inch Nails had some success, other labels asked, "Who sounds like them?" Do I think that Stabbing Westward and Gravity Kills were part of that? Yeah, I do. Were they ripping me off? Yeah, I kind of see that, and then I think, "Do I whine like that? Am I perceived as that?"

I think there's few innovators and many imitators. It shocks me to see Bush go to No. 1. Not to single them out, but I just can't respect them. Do they write good songs? Yeah, they've written some good songs. But I cannot respect or tolerate the lack of innovation.

Music is my life. I know everything I can know about it. I know that it's not background. It's not stuff you put on in the car to drive home from your job at IBM. It means something to me. And that's why I hate when something so uninteresting can be so successful. But I'm going into it with this purist attitude. I can see that Bush song as exactly this Nirvana song. I can tell. Fuck them for doing that, you know? But it's also well-written enough that a guy who comes home from work can say, "Yeah, that's a good song. These guys rock.

Exactly. It may be good music but it's not important music.

You've got a point there. From Stone Temple Pilots on down the line, they've got some good songs give them credit but their whole premise, the house they built, is ridiculous. They're not saying anything. I don't mean to sound like "I am important." I rip people off, too. People always say about our music, "Yeah they're just Ministry songs. But if I started thinking, "Fuck, that's a good song. I should write one that sounds just like it," or "I should cut my hair like that, maybe then I'll be successful," I wouldn't have a soul.

Do you think people can tell the difference between what's sincere and what's a pose?

I'd like to think they can. But the English press gives me all this shit, "No one can be as depressed as this guy. He's full of shit. He's just cashing in." But I am that depressed! My head's just wrong. I'm not trying to be Mr. Tortured Artist Guy. I wish I could be more content with the situation I've got. It's a complicated situation, and I see contemporaries who are very happy in the situation they've got. But my head doesn't work the same way.

But is being "content" something you should necessarily strive for?

It's not about being content. It's about, What if everything you ever wished for in your life and never thought you'd get, you got? And it Still sucked. That's the thing I look at Oasis: dumb idiots just living life. You know, ignorance is bliss. And there's a truth to that. I guess I just don't want it.

So, do you ever feel you don't deserve to be a rock star?

I'll say one thing here. When Nine Inch Nails first got signed I didn't know how to do interviews. I really still don't. I talk too much and I say stupid things. At the time, my heroes were Jane's Addiction, among others, and I'm reading where Perry's a male prostitute and has this junkie lifestyle. And I'm like, I smoked pot when I was 18 once. I'm boring. I'm not this icon. I love Kiss for the same reason. Gene Simmons had a cow tongue grafted to his; that was the greatest shit. And I kind of made this pact with myself that I would just be honest. I am 31. I grew up in Pennsylvania. I wasn't a male prostitute. I'm not gay. My tongue is my own. It's not like a Marilyn Manson situation. I love Manson, I respect him. He's about show biz and he knows what he wants to do. And I think he's a good kick in the ass of that conservative Pearl Jam pseudo-alternative integrity thing.

How much of what's going on pop-wise do you view as competition?

I watch MTV and I think it sucks and I think most videos are shitty. But I watch because I like knowing what's going on. I want to know that the last No Doubt video sucked so I don't do it myself. Since I'm aware of the business element of things, I get to feel a little competitive For example, I like Beck now. But when he first came out, I felt that "urrrrggghh,” just purely from a he's-the-competition point of view. Not that we're doing the same thing. I felt stupid even feeling that. But I wanted to not like him. And then I was like, "Your shit's good." Everyone around me says he's great, he's great. And I think that last record is great. But it's hard to not feel that sense of competition. It's a bullshit way to think. And that's what's disturbing about that whole idea of "You're number one." Well, why? Because I’m better than him? I try not to think that way, but to be frank, there's a part of me that does feel that.

Have you considered doing something completely different, like a record as Trent Reznor instead of Nine Inch Nails?

I've thought about that. I'd really like to get into more film scoring. I think I'd be good at it. I also thought about doing a record of instrumental piano, like This Mortal Coil-type mood music, music you can put on when it's a rainy day. Or doing things like [the sounds on the CD-ROM game] Quake.

Do you ever go to the game areas on the Internet under an alias to post messages asking for help when you're stuck in a game?

Oh yeah, totally. I'm a cheater. And I'm a videogame addict. I could have written 15 more records in the amount of time I spent playing Doom.

Do you ever worry that something or someone is going to cut short your life before you've said everything you have to say?

Through my own self-destructiveness, or through a random act of violence?

Either.

There's the whole romantic notion of Ian Curtis, or for that matter Kurt Cobain, burning out before they've said what they've had to say. But I don't really think about it that much. I've got a long way to go in terms of what I want to accomplish. I've got a lot more I really want to say. I'd be sad if I were dead tomorrow, though [laughs].

Live! Magazine, January 1997

Thanks to Mark for the Live! cover shot.

"Nailed Down"

-By Ben Sandmel

With a new studio and a 19th-century mansion, Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor joins the parade of edgy artists who have planted roots in New Orleans.

New Orleans is renowned as the home of classic jazz, Creole cuisine, ornate balconies in the French Quarter ... and Nine Inch Nails' new studio and headquarters? Yes, add Trent Reznor to the long list of creative types - from Lafcadio Hearn, William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams to Bob Dylan and Daniel Lanois - who fell for the city's exotic ambiance and decided to settle in for a spell.

It's been a long journey - from his high school band in rural Mercer, Pennsylvania, to the Cleveland club scene where this self-described "computer dweeb" forged his personal blend of hard-core and industrial sounds. Reznor, a one-man band in the studio, emerged in 1989 with the million selling Pretty Hate Machine, following with the equally uncompromising Broken (1992) and The Downward Spiral (1994). He broke out of the pack of alternative rockers with electrifying performances during the first Lollapalooza tour in 1991. Los Angeles Times pop-music critic Robert Hilburn called his appearance at Woodstock 2 in 1994 "a marvelous reminder of rock's rebellious roots." The following year, after a period in Los Angeles, Reznor was in search of an inspirational place to live and work. New Orleans was the perfectly logical choice.

Not that Reznor's computer-crafted sound and tormented lyrics owe much to such Big Easy icons as Fats Domino and Louis Armstrong. "At least not on a conscious level," Reznor comments, ensconced behind the 48-track board in his recently installed high-tech studio. "I'm not really familiar with the music scene that exists in New Orleans, and it's not what I moved here for."

"Moved," in Reznor's case, refers both to the 19th-century Garden District mansion he calls home and the elaborate recording/rehearsal facility he set up in a former funeral home uptown. Just a few blocks from the nightclub and local-culture bastion known as Tipitina's, Reznor's studio has no formal name and no sign out front. But the spiffy new paint job - in a rather mundane shade of brown - makes it obvious that the two-story building has just been renovated. Such squeaky-cleanness stands out in a town that celebrates decaying grandeur, especially on a block that also boasts a homemade praline stand and several funky antique shops.

These atmospheric touches are more typical of what Reznor moved for - the profound and pervasive weirdness that is one of the city's less touted but most striking features. In New Orleans, the four points of the compass are useless in determining direction; logic and efficiency defer to whimsy and indulgence. It's the kind of city where even the decadent eccentricity of Reznor's controversial "Closer" video would barely raise eyebrows. New Orleans lies well outside of America's cultural mainstream and work-ethic mentality, a fact celebrated in S. Frederick Starr's New Orleans Unmasqued - which Reznor recently purchased - and John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces. In this spacey, sensual environment, an enterprising artist can work hard and draw on the rich local vibe yet avoid most of the intrusive trappings of a major industry scene.

All of which suits Trent Reznor just fine. "I feel creative here," he says, "rather than oppressed by the big-city feel and the music business - I hate all that shit."

In contrast to the hard-core feel of his music and videos, Reznor is not the least bit ominous in conversation. Bright, direct and articulate, he comes across as focused and professional. Inside, Reznor's studio emanates a similarly businesslike attitude, with muted mauve carpeting in the office and the healthy 90's touch of an elaborate weight room. There are traces of youthful indulgence and techno-culture in his extensive collection of video games, pinball machines and vintage arcade games. The basement garage - once home to a fleet of hearses - now houses several pricey cars.

A few bizarre items are to be found, most notably a door from the Sharon Tate mansion in Los Angeles, site of the Manson Family murders, where Reznor lived while recording The Downward Spiral. What was once the casket elevator is now used, pragmatically, to move heavy gear. But the studio's most notable feature is a sophisticated and seemingly endless array of sound equipment, enough for two complete recording studios and a digital-editing suite.

Sitting at the center of this sonic universe, Reznor continues to contemplate the world outside his door. "I like the fact that New Orleans is still kind of a small town," he says. "There are parts of the small-town mentality that I'm really comfortable with. But the small town where I grew up in Pennsylvania has very long winters, and there isn't much sense of culture and tradition. It was ultraconservative and stifling. New Orleans is just the opposite. It feels like a European city. I find it relaxing. I like the weather, the architecture and the way the city looks. And I like the fact that when I'm stuck on something I can just go ride my bike and find a sense of space - I'm not oppressed here.

"There's also a weird sort of spirituality in New Orleans," Reznor reflects. "I'm not talking about the spirit world that exists in Anne Rice's books, although some people see a connection between our work." So much so that groups of young, black-clad tourists see roaming the Garden District are usually hoping for a glimpse of Rice, Reznor or both. "There was a time in my life when Anne Rice's books were interesting to me," he explains. "That was before I moved here, and I suppose that in a way they tainted my first impressions of the city. But I'm out of that now. The spirituality that I'm talking about is the personal freedom, the strangeness. So I'm definitely influenced by New Orleans in that it puts me in a good frame of mind to work."

And work is indeed what the 31-year-old Reznor does. Disturbing though that work is to many people, it's also extremely popular and lucrative. Reznor's skills are in great demand. He produced Antichrist Superstar, a record by shock-rock brats Marilyn Manson, and will soon start on a long-awaited Nine Inch Nails album. There was also talk of a soundtrack project for a Robert De Niro film, following a similar assignment on Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers.

Such weighty projects call for serious gear, and Reznor can will afford to be picky. "When I decided that I wanted to live in New Orleans," he recalls, "I found that none of the studios here really met my needs in terms of equipment, especially since I do most of my recording in the control room. I had been thinking of creating a space that could be a complex for Nine Inch Nails, where we could make noise, rehearse, record, have several different things going on at once. I wanted to be self-sufficient. So far the studio has been used mainly for my projects, although Pantera did come in and work for a few weeks, and Coil may book some time.

"But I'm not really into the idea of being a studio owner and renting the place out," Reznor emphasizes. "What's the point of setting all this up if I can't get in and use it when I want to? Eventually, though, I may open it to selected clients."

With big-league projects stacking up, Reznor is hardly a club-hopping man-about-town, though he does have a penchant for a French Quarter restaurant called NOLA. "But as for hanging out or interacting, I'm not really tied in to the local scene right now," he says. "I don't mean that in a standoffish way; I just work a lot. I think that my studio could eventually become a part of the local scene and offer something really modern that hasn't existed here before. If that happens, it would change the preconception that all music made in New Orleans is jazz or rhythm and blues.

"Of course," Reznor hastens to add, "people like the Meters and Allen Toussaint are really good. But there are many other things going on here as well. And," he concludes with grand understatement, "the nature of what's classically known as New Orleans music is certainly a far cry from what I'm working on over at my new place."

This article was originally available here at the Cleveland Online website. It gives a history of Trent's pre-NiN days in local bands of the Cleveland music scene.

Trent On Tour With The Innocent, 1986 |

Down In It:

Trent Reznor in Cleveland Nine Inch Nails are known across the world now, but before he made it big, Trent Reznor was a major player in the Cleveland scene. Before there were the Nails there was... | |

The early-'80s: Growing up in a small Pennsylvania farming town, Mercer, Pa., as part of a family who owns the rights to the Reznor furnace (an industrial heater), Reznor left for Allegheny College, where he studied computer engineering for a year before dropping out and moving to Cleveland.

The mid-'80s: After playing in a Top 40 Cleveland cover band called the Urge, Reznor joined the Innocent, a mainstream rock band a la Journey or Foreigner, with whom he played keyboards and sang. The band signed to the Chicago-based Red Records, a label whose only previous release was the "Superbowl Shuffle", a platinum selling LP recorded by the Chicago Bears. Reznor performed several live shows with the group, including some opening slots for Bryan Adams.

The late-'80s: After leaving the Innocent, Reznor worked at Pi Keyboards, a store on Brookpark and Broadview Roads (in Cleveland) that sold and repaired keyboards. He also got a job as an engineer at Right Track, a downtown studio known for recording Levert. Reznor soon hooked up with the Exotic Birds, a dance-pop band led by Cleveland Institute of Music percussion major Andy Kubiszewski (who would later play on NIN's Downward Spiral). He joined the Birds as they were moving towards a more-textured synth-heavy sound, and played on the group's second LP, L'oiseau. After the group disbanded (temporarily) in '87, Reznor joined the Top 40 synth pop group Slam Bam Boo, with whom he released a 45, "White Lies" b/w "Cry Like A Baby." A subsequent group, started by Slam singer Scott Hanson called Hanson: the Movie, had Reznor doing computer programming and engineering. During this time, Reznor also made a cameo as a member of Michael J. Fox and Joan Jett's back-up band (with Nation of One's Mark Addison and fellow Exotic Bird Frank Vale) in the 1987 film Light of Day, shot at many Cleveland locations including the Euclid Tavern, where the movie band played.

After playing some shows with Lucky Pierre (singer-guitarist Kevin McMahon was living in San Francisco, but would regularly return to town to play live), Reznor then played keyboards on the group's 1988 Communique EP, the title track of which would later appear on the debut of the McMahon-led Prick. (Reznor was also roommates with Lucky Pierre bassist Tom Lash, later of Hot Tin Roof).

Meanwhile, Reznor was working on his own recordings during off-hours at Right Track, doubling as a janitor at the studio in return for the free recording time. The result? The demo for Pretty Hate Machine, the tape that got him signed to TVT Records (short for TeeVee Toons), a label whose main notoriety involved releasing Television's greatest hit theme-songs. He then assembled a band, his first of many temporary line-ups, including former roommate Chris Vrenna (drums) and Richard Patrick, a guitar player in the U2-sounding group the Act (who would later found Filter).

NIN-'90s: After Pretty Hate Machine--which was produced by Flood (of U2 and Depeche Mode fame)--his contract was picked by Interscope Records. In 1992, Interscope gave Reznor his own label subsidiary, Nothing Records, which would go on to sign McMahon's Prick and is co-run by John Malm, who had managed both the Exotic Birds and Reznor in his early-solo days.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Above The Trees: Proudly Serving The Ninternet Since February 2, 1997.

This site created, designed, and maintained by Rob Sheridan (xott@nwlink.com)