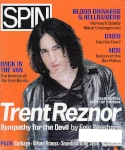

Sympathy for the Devil

-By Eric Weisbard

POLITICAL OPPORTUNISTS MAY HAVE BRANDED TRENT REZNOR MORALLY REPUGNANT, BUT YOU BRANDED HIM SPIN'S ARTIST OF THE YEAR. SENIOR EDITOR ERIC WEISBARD JOURNEYS TO REZNOR'S ADOPTED HOME, NEW ORLEANS, FOR A ONE-ON-ONE WITH ROCK'S REIGNING KING OF PAIN.

Trent Reznor is running victory laps these days. I meet him just as he's finished an American tour with David Bowie; Nine Inch Nails, though technically the opener, provided the commercial clout necessary to fill stadiums and amphitheaters. Now, purely to satisfy a nostalgic craving for NIN's early years, when their constant touring metamorphosed the agitated synth-pop of "Head Like a Hole" and "Terrible Lie" into a clomping rock'n'roll animal, Reznor is taking his band through the South for a series of club dates. After that, he plans to return here to New Orleans, finish remodeling a two-story mansion in the Garden District, hook up the boards and wires in his almost equally large personal recording studio on Magazine Street, and comfortably begin the process of recording a sequel to The Downward Spiral.

That new album will undoubtedly debut at the top of the Billboard charts; Reznor has money to burn right now, and he wouldn't be Trent Reznor if he didn't throw himself into the fun. Our first encounter comes at Nola, an upscale restaurant in New Orleans's French Quarter. In honor of the tour hitting Reznor's adopted city, 16 or so band members, roadies, security guards, bus drivers, publicists, road managers, and an allegedly transsexual girlfriend of the keyboard player join Reznor for turtle soup and belts of a toxic tequila variant. The dinner stretches on for over two hours, the conversation purple enough to arouse people for whom partying is just another day at the office. Accordingly, Reznor genially recalls for me an earlier tour, where the Jim Rose Circus accompanied NIN and held vicious after-show fests; one time, three groupies ate Froot Loops out of a bowl on the ground, submitted to enemas, and were then matched up in a shit-stream competition.

Oh, great. Is it too late to join up with C. DeLores Tucker and Bill Bennett in the campaign to remove sick weeds like Trent Reznor from our culture? Does Reznor realize that he and his crew are recreating every tired cliché of rock guys on the road? And how do such retro tendencies fit with his music, which has done more to import the aggression of rock into the age of synthesizers and computers, which is to say into the future, than anyone else's?

Well, maybe there's a touch of the groupie in me too, because I'm not bothered as I should be - Reznor has seduced me with his smile. It really is remarkable, a beam of approval he turns on people that says forget my celebrity, I'm working harder to please you than you are to please me. Some rock stars have enough offÂstage charisma to hold your attention no matter how big the crowd; as I sit next to Trent Reznor my eyes dart all over the room. He's not exactly "one of the guys" - more the sort to surround himself with people weirder and crazier than he is, knowing he'll keep alive by trying to keep up.

So while it's certainly reasonable to disagree with Reznor's cruder perversities, his enthusiasm for the bad life belies any simple charge of pandering. After dinner, Reznor's longtime friend (and NIN drummer) Chris Vrenna drives us to see Reznor's new home. (En route, Reznor plays around with the car's CD changer; he calls up "Nightclubbing," off The Idiot, the album David Bowie produced for Iggy Pop, and points out the opening beats: "I stole that for 'Closer.' ") A spacious Greek Revival, his new digs feature foyer walls colored with what looks like speckled blood, a soon-to-be downstairs entertainment complex (supplied as a gift by his label, Interscope), balconies and floor-to-ceiling windows ringing the second floor, and a bathroom off the master bedroom bigger than many Manhattan apartments. Still, unlike more reclusive celebrities, Reznor will live on a residential block, with other homes across the street and next door. The local New Orleans newspaper rewarded this bit of humility by running a photo of the house, naming the street, even, on their Sunday front page.

We talked from one A.M. until four that first night. Two days later, following a surprisingly limber club date by NIN - all the anthems the Bowie tour omitted, all sorts of funky little outros and revamps, and a Queen cover - we finished the conversation in Reznor's new studio complex. The second-floor office is right next to an area that houses Reznor's collection of vintage video arcade games (he's also a big fan of the computer game Doom, and is writing the music for its sequel, Quake), a Kiss pinball machine, and the torture chair from the "Happiness in Slavery" video.

SPIN: Hanging around you and your entourage, I felt like I was watching a throwback version of the rock'n'roll lifestyle.

Trent Reznor: I'm the guy, if someone calls me at three in the morning, "Hey, come do something." "No." "Come on." "All right." Why not? I'd like to bow out thinking, hey, I did that. I tried that. I experienced that. I wasn't afraid. Rather than sit in the back room with a fucking towel over my head, I want to be be around it, absorb, consume.

When I get off the road, I'm not good at making tons of friends. I'm not great at entertaining people. When I'm doing a record, I don't ever go out. The real me gets up at a regular kind of schedule, writes music, and doesn't party all the time. On the road I adopt a certain kind of mentality. A lot of it is juvenile, but it's also about staying sane in an insane situation.

It's politically incorrect these days in the alternative world to indulge and have fun in a touring situation. Certain camps, like Courtney Love's, like to say we're a horrible, ridiculous throwback to cock-rock bullshit. That's not what we're about. But at the same time, if there's fun to be had, why not? Nobody gets hurt. And I'm not going to be doing this forever.

One thing you told me that horrified me was that story about the Jim Rose after-show party. Women competing in enema contests, and such. You can say that's not different from wanting to stay late and party, but are people drawn to be around celebrities at any cost really willing participants?

Remember, you've got to put this in the context of what's going on. It's not ten guys waiting to date-rape drunk groupies. That is not at all the situation. Lifto [from the Jim Rose Circus] - he can't do his lift-an-iron-with-his-dick trick onstage, so he can't wait to do it for me backstage. He's walking around with his dick, that long. Naked. There's 20 drunk people sitting in the room. It's a party atmosphere. I walk in, and they've got this stun-gun out. Pretty soon, 20 girls are getting shocked in the butt. And another guy gets his dick ring shocked with it. Retarded. That's the kind of vibe that we're talking about. Outperform the performance artists. That's where it turns into the dare of "who's going to get more gross than the next person?"

Where does that leave you? It doesn't seem, from your personality and your behavior, that you're one of the participants.

I'm not getting shocked. It wasn't me sitting over a bowl of Froot Loops. I'm much more a voyeur. It's more fun than riding the bus back to the hotel. Or sitting in a bar with 500 people wanting your autograph while you're trying to relax.

On the Bowie tour, his band hung out in our dressing room all the time. They didn't want to sit around, reading poetry and talking about fucking German art movies. They wanted to hang out.

How did you go from being a kid in rural Pennsylvania to the party option on a David Bowie tour? What was the musical process?

When I was five, I got forced into taking piano lessons. And it came really naturally to me. Knowing that I was good at something played an important role in my confidence. I was always shy, uncomfortable around people. I slipped by. But with music, I didn't. I got into bands. I studied trumpet and saxophone a little bit. It got to the point where my teacher was like, you can be a concert pianist. But the last thing I wanted to hear, at age 15, is, well, you're not fitting in now, how about dropping out of school, studying all the time, and becoming a concert pianist? It sounds like "penis."

Even earlier, Kiss had changed my world. It seemed evil and scary - the embodiment of rebelliousness when you're age 12 and starting to get hair on your balls.

Also, my dad, who I'd not lived with since I was five, got me an electric piano. He had a little music store that sold acoustic instruments in the back room, where me and a couple other guys started jamming in terrible garage bands. I realized that music wasn't all about learning a piece on the piano.

You never felt snobbery towards rock?

No. On piano, I had a fairly knowledgeable database of theory. But I started fucking around with guitar, and I was never good at guitar. I'm still not good at it. I took lessons off my dad for a couple of months, and then said, "Look, I'd rather just fuck around on it, and not know." I still only know two bar chords. But I don't care. The naïveté with which you approach an instrument can lead to interesting results, versus the schooled "you can't do that."

Was punk an influence even then?

No. You have to understand, I was in a geographical area where by the time I'd hear something it was already dead. There was no college radio. There were no alternative record stores. There was no independent anything. There was no MTV. There was nothing. My world was comic books and science-fiction shit. Scary movies. Whatever I could absorb. And it kind of ingrained in me this idea of escape from Pennsylvania.

What was the first real rock band you ever played in?

Option Thirty. That was actually about one-third originals, two-thirds covers, from Elvis Costello to Wang Chung. For what it's worth, Wang Chung put a record out before the "Dance Hall Days" record, when they spelled their name differently. H-U-A-N-G Chung. All guitar-bass-drums. Still a real good record.

When did you start playing synthesizers?

When I was in high school, I begged my parents to get me a real cheap Moog. Now I could play "Just What I Needed." Whoo-oo-whoo-oo. [Whistles synth line from the Cars song.] When that kind of explosion of synth music came around in the early '80s, it really was exciting; sequencers were just coming out. I was going to college for computer engineering and I thought, I love music, I love keyboard instruments - maybe I can get into synthesizer design. The excitement of hearing a Human League track and thinking, that's all machines, there's no drummer. That was my calling. It wasn't the Sex Pistols.

What's the lowest point music has led you to?

When I dropped out of college, which would have been the year of '84, I spent a year doing nothing. I lived with my dad out in the woods. And I was playing with cover bands. Three hundred bucks a week. It was the most whorish part of my career so far. I played keyboards and sang. My destiny was lounge bands.

So how did you break away?

I moved to Cleveland, because the band I was in was playing there a lot. There was a music store that had all the high-tech synthesizers and sequencers that were coming out. I was there all the time. They offered me a job. Ten to six, every day. Hearing 20 people bang on drum machines.

One of the guys that also worked at this store was in a synth-poppy, all-original band called Exotic Birds. I got a job with them as a keyboard player. The band eventually became me playing all the keyboards, the main guy writing the songs, singing, and playing guitar, and Chris Vrenna, my current drummer, playing drums. That's also when I met my manager, John Malm.

Had you written a single song, at that point?

No, I hadn't written anything. Ever. I'd never written a song. I was afraid. I always had an excuse not to do it. One day I woke up and said, "You're twenty-fucking-three years old, what the fuck are you doing? Shit or get off the pot." So I quit Exotic Birds and got this job doing odds and ends at a studio. And I made a pact with myself. I'd been getting high a lot. I was turning into what I'd never wanted to be. So I started this experiment: What would happen if every ounce of energy went into something? Because I'd never busted my ass.

I eventually had no excuse for not actually trying to write something. My very first song was "Down in It." At the time, I was really into Ministry and Skinny Puppy - in fact Skinny Puppy's "Dig It" was the impetus for "Down in It," I'm not ashamed to admit. Finally, I was hearing bands that were using electronics, and they didn't sound like Howard Jones or Reflex. They had all this fucking aggression and tension that the hardest of heavy metal or punk had. But they were using tools I understood. And it seemed more interesting, because this music couldn't have been made five years ago, let alone 20. It was based on tools that were now.

But unlike bands like Ministry or Skinny Puppy, your lyrics were confessional - you sounded like a rock star from the beginning.

It was all stuff out of my journal. This wasn't a character singing lyrics. This was my guts in a song. I still think about that, sometimes. Now, Pretty Hate Machine has sold a ton of copies, and I'm dismissed by some as a caricature or a cartoon. But when I wrote this thing, that wasn't a character singing. And I didn't know if I wanted people to know that much about me.

Talk about the recording of Pretty Hate Machine.

We had one month in England to do practically the whole album. John Fryer, the producer, and I didn't hit it off. We didn't work on weekends, because he's "a normal guy." So by the second week there I was dreading weekends. I didn't know one person in England. And I'm not the kind of guy who could ever go to a club in another country by myself. I started getting bummed out, thinking, I've got two more days of nothing to do. I'm staying in this shifty little flat. It's cold.

Here is the fucking icing on the cake. Before I decided I was going to stop my life and do this, I had this really great ex-girlfriend - let's call her Patti. Right before I left to go do this record, I saw her at a club, and she looked better than I ever remembered. We had a nice little talk. So the whole time I'm gone, while there was nothing else to think about, I started thinking about her. When I get back, I've got to make this happen.

So, it's a Friday, and I've got a full weekend ahead of me, and I'm ready to tell John [Maim], hey, try to get her number, because I need to talk to her. In the middle of the conversation he goes, "Oh, by the way, I saw Patti last night." "Oh, you did? How is she?" He said, "Man, you'll never guess what." "What?" "She's pregnant, and she's getting married." I literally thought, "God, fuck you. You got me, you fucker."

And then I go back to the States, and the label tells me, hey, by the way, this record is a piece of shit.

Ultimately, Nine Inch Nails established its reputation as a touring band, with manic live shows, which is also unusual for electronics-oriented music.

I was from the Todd Rundgren school. The studio is an instrument. Manipulate it, don't go in thinking it's got to sound like my band. When I got done with Pretty Hate Machine, I realized, "Holy fuck, how am I going to play this live?" I knew I didn't want to go out and do a Nitzer Ebb, two guys standing there kicking pads. I like electronic music, and I hate that sort of thing. I also didn't want the record to be one nerd with a synthesizer, but live for there to be a David Bowie-type backup band, 15 people and a horn section. I use electronics because I want to - not as a compromise for something else.

So, after much experimentation, and trying to find the right people, I thought, we'll get a drummer, guitar player, keyboard player. And I'll play the occasional guitar. Put the bass on tape. Or sequenced. And sequence some of the loops, in the background, stuff that's unplayable anyway. That, ideally, will maintain that mechanical element that's in there. But maybe it will come to life with real people playing.

It's almost like there's a contest going on between humanity and the machine.

Yes. As it was when I did the record - Pretty Hate Machine was about juxtaposing human imperfections against very rigid, sterile, cold arrangements. You can't just have icy vocals over icy music. If the music is very precise, make a vocal tape that's less perfect, so you've got this meshing of man versus machine.

Much to my pleasure, after a few months of touring, it really started to work. The songs started to take on a new life. Those were probably the best times of my life, when we first started touring. At that time, it was Chris on drums, me playing guitar a little bit, this keyboard player, and Richard Patrick, who's now in Filter, playing guitar.

Was it strange when Patrick made that Filter record, and a Nine Inch Nails-sounding record at that?

Rich was this friend, and he played in the band for a while. A pretty good guy. We were going to work on Downward Spiral together. But he wanted to be the guy that got recognized for writing the songs and singing. I didn't realize his real agenda was to have a way out to L.A. to get a record deal for himself.

There hasn't been any reconciliation?

There's been a drunken phone call to me to say hello. And then asking an ex-girlfriend of mine out on a date. Those guys. In their minds, they're stars.

Anyhow, we started in January of '90, opening for the Jesus and Mary Chain. Toured with them for six weeks. Right after that, we went right to Peter Murphy. Two headliners that weren't difficult to blow off the stage. And then it took over. This weird fucking energy and negative-energy release, this purging exorcism that takes place onstage.

Who is the creature you become onstage?

That's the me that's allowed to act. OffÂstage, I'm always trying to be nice to everyone, trying not to be - let's say you really respect somebody, and finally you get a chance to talk with them and they're a dick. I'm so aware of that, and I overcompensate. I know what it's like to be a fan. But it's not really how I want to act, you know what I mean? I've just finished a fucking show. I don't care that you want to kill yourself. I'm sorry. Too bad. No, don't give me your poetry. And, no, I don't want to go and do drugs.

But the you that's onstage doesn't have to be that nice.

No. He can do whatever he wants. There's this weird kind of energy that just pops up when we do a show. There's a level of connection that starts to happen. Something about looking out and seeing a bunch of kids screaming back a lyric that at one point meant everything to you. Pink Floyd's The Wall changed my life when I was growing up. Even if I didn't have any idea of what they were really talking about. I've probably listened to that record a million times. Even now. The alienation factor. Man, someone else went through that. I think I see some of that vibe in people with our stuff. And that makes me feel pretty good.

What you do live hasn't changed as much as your particular records.

I agree. The three records have different focal points, or viewpoints: Broken's central theme is self-loathing; on Downward Spiral I'm searching for some kind of self-awareness; and on Pretty Hate Machine I'm depressed by everything around me, but I still like myself. I've still got myself. On Broken, I've lost myself; nothing's better, and I want to die. Downward Spiral was searching for the core, by stripping away all the different layers. But live, the lines aren't as clear-cut.

How did playing on the first Lollapalooza tour affect Nine Inch Nails?

The entertainment factor of our show got proven at Lollapalooza. We'd filtered into mall culture a little bit. For a while it was trendy to like our band. Then that quickly got dismissed, because the little sister of the trendy person started wearing a NIN T-shirt, and then we weren't cool any more.

In retrospect, was it fun to be part of that first tour?

Aside from Henry Rollins deciding he hated me, it was real cool. Particularly as a fan of Jane's Addiction - I'd seen them when they first started touring on Nothing's Shocking, in small clubs in Cleveland. And I could not believe how good it was. It kicked my ass.

It must have been new to you to have other musicians as peers.

I was real freaked out by it. What do I really have to talk to Siouxsie about? Like the Jane's Addiction guys. Perry had too many people's heads up his ass on that tour to ever really communicate with him. But the other guys are really nice, sweet guys that I could have formed good friendships with. But I always felt nervous around them. I still remembered that club show.

Has it evolved, now, to where you're comfortable in those kinds of settings?

More so. But on this tour with Bowie, I found myself kind of hoping that he wouldn't be sitting there, so I wouldn't have to talk to him. Not that I didn't like him. But I felt like I had to impress him. I had to impress his band. I couldn't just let my hair down.

Who are some of the musicians who you've come to think of as friends?

An odd bunch of people. I think the guys from Pantera are cool. Everyone from Tommy Lee of Mötley Crüe to Adrian Belew. I met the guys in the band Live because we were playing at festivals in Australia. All of them are people I wouldn't hesitate to say, let's work on something.

Like you did with Tori Amos.

Tori would be another example. She called me to do this vocal track. It wasn't that big a deal. Her first album was permanently in my car's CD changer. It really struck me as well written, in a similar vein to what I was doing - from a different point of view, but the same kind of addicting, pouring out, gushing, baring, naked kind of song. Other people put their fingers in the pie, and they kind of messed up a friendship. We're not that close now. Some malicious meddling on the part of Courtney Love. But I still feel the same feelings for Tori.

How did the success of Pretty Hate Machine and your Lollapalooza tour produce a tormented record like Broken?

On a personal level, I was coming out of a weird relationship. I really fell in love with someone and we lived together for six or eight months. But it went from being the best to the worst. Plus, I hadn't spoken to the label since before Lollapalooza. We made it very clear we were not doing another record for TVT. But they made it pretty clear they weren't ready to sell. So I felt like, well, I've finally gotten this thing going but it's dead. Flood and I had to record Broken under a different band name, because if TVT found out we were recording, they could confiscate all of our shit and release it.

Jimmy lovine got involved with Interscope and we kind of got slave-traded. It wasn't my doing. I didn't know anything about Interscope. And I was real pissed off at him at first because it was going from one bad situation to potentially another one. But Interscope went into it like they really wanted to know what I wanted. It was good, after I put my raving lunatic act on.

Is Broken, then, the summation of your personal problems, or is its noisiness a spit at the Lollapalooza crowd?

I wanted to be tough. I was so concerned about staying "alternative," that indie bullshit mentality. After Lollapalooza, I had this snotty elitist mentality - you're not cool enough to like my band, don't buy my records. I wanted to make a "fuck you" record. It was also a bit of a knee-jerk, "I'm not a pussy," "I'm not a sell-out" attitude.

After it came out, I wanted to start work right away on a real album. I had been working on the idea of Downward Spiral in my head for a while without writing any songs, just a concept. Originally, my pretentious aspirations were to make the dreaded concept record with a film that went with it. Derek Jarman was interested in doing something. Again, you could maybe hark back to The Wall as my inspiration.

What was the crude, stick-figure version of Downward Spiral before you'd even written the songs?

Well, I wrote down a bunch of topics I wanted to address. And key events in my life. A mom and dad getting married because she's pregnant - like Patti, when I was in London doing the record. Weird little displaced memories that conjure up emotions. Not always upsetting or unhappy. I remember walking home from piano lessons at age 10, 12, a weird, euphoric feeling. Life is good. So in my notebook there was this huge page of stuff.

Let me ask you about Downward's "Big Man With a Gun." I'm sure you've heard the story of C. DeLores Tucker going to the Time Warner people and saying, "Could you read these lyrics out loud?" And they refused. They are crude lyrics.

Absolutely. The record was nearing completion. I had written those lyrics pretty quickly and I didn't know if I was going to use them or not. To me, Downward Spiral builds to a certain degree of madness, then it changes. That would be the last stage of delirium. So the original point of "Big Man With a Gun" was madness. But it was also making fun of the whole misogynistic, gangsta-rap bullshit.

Really! The song was a satire of gangsta rap?

In a way. I listen to a lot of it, and I enjoy it. But I could do without the degree of misogyny and hatred of women and abuse. Then, my song got misinterpreted as exactly that. It was probably a lack of being able to write. I've been taken out of context, and it's ridiculous.

C. DeLores Tucker, I think, would be stunned to hear that to some extent she has an ally.

Well, she's such a fucking idiot. But I think The Downward Spiral actually could be harmful, through implying and subliminally suggesting things, whereas a lot of the hard-core rap becomes cartoonish - it's real to youngsters, but it's so over the top. From an artistic point of view, if I'd had a couple more months to look back on everything, I probably would not have put that song on the record. Just 'cause I don't think it's that good a song, not because I got spanked for it.

But the sickest lyrics you could come up with might now be the commercially best-selling. So where does the issue of responsibility come in? Like the Amok Press T-shirt you're wearing, and their slogan "the extremes of information in print." This notion that something that's the most extreme is the best. Is that sensible?

Growing up, I so wanted to get the fuck out of where I was, away from the mediocrity and mundaneness of rural life. Anything extreme caught my attention. I was intrigued with the limit, the movie that scared the shit out of me, the book - I had a huge collection of scary comic books when I was a kid. What's the next step beyond? What's beyond Stephen King? Clive Barker. What's beyond that?

Nine Inch Nails deals with that addictive part of my personality. How many mushrooms can you take? What happens then? What about mushrooms and DMT? Nine Inch Nails offers me the chance to do what I want to do. I want a show, a spectacle. I'm allowed to look stupid. And I want to.

You did the soundtrack for Natural Born Killers, a movie about America's fascination with the edge. Is Nine Inch Nails part of the America that Oliver Stone is seeing? Is it outside of that?

Probably not. If that didn't exist, we probably wouldn't exist. But I don't think that we're just shock and carnage for shock-and-carnage's sake. I think there's more to Nine Inch Nails than looking at the wreck on the Interstate. You want to turn your head and look, and hopefully see blood. There's an element of that fascination that has been worked into the imagery I've surrounded myself with, in music. It fascinates me, to a degree. I still watch Cops.

At what point does this stuff get boring? I mean, if you've read your James Ellroy novels and you've seen Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, at what point is this ideal of finding the most transgressive thing out there conformist in itself?

It's just something that interests me. There's probably a psychological reason. I see it coming up in different things I do. Even sitting in the studio, I think about what's the most fucked up, slowest, and loudest song I can possibly record. Pushing boundaries, doing things you're not supposed to do. Incorporating shock value so you end up saying "I want to fuck you like an animal," and the chorus of the song is not subtle. It's a mechanism.

Is it possible that, when you're working musically, you wind up with more nuanced, ambiguous, complicated work, because you're so schooled in music, but when you're writing lyrics or doing something theatrical you're not quite at the same level as an artist?

That's a fair thing to say. Musically, I'm always striving to go a little deeper. Playing mental games. Like when I wrote "Sanctified," I thought, "Can I do a song that only has one bass line and never changes through the whole thing?" My idea for the next record is to build more in the song format, instead of starting with a noise or a drumbeat. I'll do things like use a different sequencer to write, so I won't know how to work it as quick and it slows me down.

On Downward Spiral I got to explore making an electronic record that doesn't sound electronic for some parts of it. We did things with drums that I don't know if anyone has really done. We sampled drums in stereo with stereo mics and discovered if you play them on keyboard it sounds like you're sitting behind the drums for real. On "March of the Pigs," "Eraser," and those songs, there's no live drums, but it alluded to being real because it didn't sound like a machine. No way someone could play that like that. It further added a kind of mind-fuck to it. Instead of falling into a Ministry-type trap of how can I make things harder and harder, it's scarier to have something creep up on you.

What was it like being the poster boy for Woodstock II?

We got there the night before, and that rave was going on. I'm glad I saw it. We slept on the bus. The next day, a power line had fallen on the bus and there was voltage going through the bus while we were on it. I went back to the bunks: "Guys, don't panic, but try not to touch any metal. There is a lot of voltage going through the bus right now." I walk to the front of the bus, and I see fucking Crosby, Stills, and Nash looking in, and a sea of cameras, seeing me in my underpants. Hi, everybody! That was the most nerve-wracking day of my life. But that changed things for us a lot, in terms of brand-name recognition.

Did you feel like, hey, I've entered this other league?

The only real time I felt like that was when Courtney Love wanted to date me. That meant I must be a star. It's a prerequisite, isn't it?

For the last two years, SPIN readers have voted you their favorite artist and Pearl Jam their favorite band. Which must mean the same people like both you guys. That's a long way from where you started. Is it strange to be part of the rock pantheon now?

I don't know that I deserve to be there. I don't know that I want to be there. Downward Spiral is pretty anticommercial-sounding compared to what's usually at the top of the charts. If ten percent of the people that bought it go "that's pretty cool," then it opens them up to realize that there is more than Candlebox to the fucking world. There is something other than guitar rock.

Pushing rock sonically into the future, away from grunge and flannel revivalism, is a real mission with you.

It is. I have a bit of a chip on my shoulder. Maybe it's from being keyboard-oriented. Not that bringing the keyboard to the forefront is one of my main goals.

The spirit of Jerry Lee Lewis. And Billy Joel.

And don't forget Liberace. Seriously, the point is more just to bring people out of complacency. Sonically, lyrically - your parents should hate it. Bob Dole should have a fucking problem with it. That's what's best about what I'm told rock'n'roll was, at one time. I could make music that I find interesting, that's experimental, instrumental noise records, and I may do that sometime. But I'm more interested, now that fate has dealt me the cards that people are interested in what I'm doing, to see how far I can push.

Take the "Closer" video. I thought, fuck it, instead of the Super 8 video directors we've used in the past, underground people, let's go with Mr. Fucking Gloss, Mark Romanek, who just did that Michael Jackson piece of shit. But he could do a beautiful shot, Stanley Kubrick-like in its attention to detail. So we decided to spend some money and go to ridiculous lengths to recreate works of artists that we liked, from Joel-Peter Witkin to Man Ray, Brothers Quay, this hodgepodge of stuff. That video was great, it was cool-as-fuck-looking. Right away, MTV said, "Can't have that, can't have that." Now okay, there was naked pussy. We knew that was going to get cut. And then we got complaints that people still found the video disturbing. "Well, why?" "Well, we don't know why, but it seems satanic and evil." And then I thought, great, we did it.

So, there's almost a double mission. Pulling rock away from the Rolling Stones tradition and bringing into the mainstream these elements of fringe culture.

Right. I think popular music sucks today. For the most part, I cannot fucking stand the shit that's at the top of the charts. Now, I'm not saying my sole mission is to turn people on to other music. But maybe I can change things a bit.

Any current bands you're proselytizing for?

In the electronic world, most people have gone the techno kind of route, which I never was that interested in. I like some of the sounds of it. It didn't hold my attention: a whole genre based on one song. However, of that genre I think Aphex Twin is a fucking genius. He's got my top billing and respect. Selected Ambient Works Vol. 2 is a better Brian Eno record than Eno's ever made. I think that's a fucking masterpiece.

What about using your visibility to champion political causes?

The idea of politics is just so uninteresting to me - I've never paid much attention to it. I don't believe things can really change. It doesn't matter who's president. Nothing really gets resolved. I don't know. I guess that's not the right attitude to take.

It's kind of the attitude of Downward Spiral. There's a real I-versus-all-of-you in that record. And not much of a we. A lot of large, impersonal forces - maybe in your music in general.

That's a fair assessment. Generally, I've always aspired to become a part of something. But I just never felt like it - it hasn't really happened. It's odd, because I have my big club, now, and I'm president. It's not like I'm a part of it, though. When I went to college, I thought that all I wanted to do was just disappear and see what it's like to have friends, be in a group. Two months later, I was like, fuck this. I'm not like you. I don't want to lose my identity, my independence, by being around a bunch of other people who are also scared, doing the same thing. Hiding behind something printed on a T-shirt that gives you a sense of who you are.

Despite your loner reputation, you seem to develop strong personal loyalties, including a group of people, from your manager to Gary Taigas who does your artwork, who go back to the early Cleveland days.

It's been nice to see the people who started off on a lower level kind of rise. We use the same manager, the same booking agent we had from the first tour, the same road manager (up to this tour). The same soundman, since the beginning. Even if it's sometimes gotten us fucked over, because everyone else in the business is bullshit, I'd rather be around straight-up, no-bullshit guys like [manager] John [MaIm]. Personally, though, I'm still a mess.

Yeah? You promise that for everyone out there?

I promise.