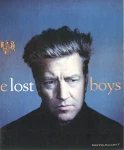

The Lost Boys

-By Mikal Gilmore

Photographs by Dan Winters

Five years after leaving "Twin Peaks," David Lynch has moved to an even darker place with his new movie, "Lost Highway." And he's taken Trent Reznor with him. THIS MIGHT BE THE STORY OF A FALLEN IDOL - A once-brilliant film director whose talents went astray and who lost his standing and esteem. Or it might be the story of a renewed hero who overcame loss and disdain to do the bravest work of his life. Given that the filmmaker we are talking about is David Lynch, perhaps it's fitting that we don't know how the story will turn out. A few years ago, David Lynch was at the height of his achievements. He had become the first avant-garde film artist to receive two Academy Award nominations as Best Director, and he had brought some of his unsettling style and vision to the recalcitrant medium of network television with Twin Peaks - a grand-scale murder mystery that became a pop-culture phenomenon. That same year, 1990, Lynch won the coveted Palme d'Or at Cannes for Wild at Heart (a film most American critics hated), and he landed on the cover of Time magazine. "It was a pretty high time," he says. "But in a high time, there's plenty of danger." It has been five years since Lynch's last movie, the much-maligned Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. The director has been relatively quiet in the interim, making commercials (Alka-Seltzer Plus, Adidas) and trying his hand at a couple of other TV efforts, which almost nobody saw. Now, however, Lynch is about to release a new feature film, Lost Highway, and it is something truly startling - a work that gives structure to the interior reality of psychosis in much the same way that Lynch's earlier movies gave form to the intangible logic of dreams. For my tastes, Lost Highway - a film about betrayal, sex, murder, deception and tortured memory (a good list, wouldn't you say?) - may be the best movie David Lynch has ever made, though it may also prove to be a major test for whatever mainstream audience he still commands. In any event, there is nothing else like Lost Highway out there, and there is no easy way to prepare an audience for its experience. LYNCH LIVES IN THE LOWER part of a hill canyon just outside Hollywood. He owns three houses in a row on the same street, and one of these houses figures prominently in Lost Highway - in fact, the house may be the film's most unnerving character. In Lynch's mind, the house had to be a certain way. He remodeled its exterior so the front featured eerie-looking slot windows, and he also added a tunnellike hallway to the place. The changes were worth the effort. The scene in Lost Highway where Fred Madison (played by Bill Pullman) walks down the house's hallway into pitch darkness is a pivotal moment: It's a portrayal of man walking into the darkness of his own destiny. Much has been made over the years of Lynch's homey manner - the way he wears button-down shirts, speaks in a Jimmy Stewart-style twang and punctuates his conversations with phrases like "golly," "righto," "you betcha" and the like. This is all true, at least as far as I could tell. There's no question that there's a profound darkness somewhere inside David Lynch, if only in his own power to imagine, but it probably doesn't come to the surface easily. On the afternoon I meet Lynch, he is dressed in a nice black shirt (buttoned to the neck) untucked over khaki slacks. While we talk, we sit in the carpentry studio that is located in Lynch's middle house. The room is full of big, gleaming machines and little items of woodwork. Lynch is 51 years old now. There are crinkles around his gentle eyes, and as he listens and speaks, his delicate fingers sometimes flutter unconsciously. Lynch doesn't seem bitter about the failure of his last two movies. "When you love something," he says, "and feel you've done it correctly, then negative criticism doesn't hurt so bad. I love those movies. But in order to say you're successful, a film has to make quite a lot of money, and I haven't really done that. If I was successful in that way, I'd be . . . I don't know, making pictures maybe more within the system." Lynch pauses and flashes a smile. "I can see how it's nice to be entertained," he says. "But there are different kinds of films. I hope it would be possible to make a film that has some depth to it but that still has a strong story and great characters, and that people would really appreciate. That has happened in history - a film made by a director where there is no compromise, and when the film was released, it worked for huge numbers of people. And when that happens, it's thrilling to the soul." IT IS TRUE THAT LYNCH'S MOVIES have never been major commercial successes. They've generally done better with critics than with audiences - that is, until Wild at Heart and Fire Walk With Me, when they didn't do too well with either. At the same time, in the 25 years that he has been making films, David Lynch has had a considerable impact on modern cinema. He has influenced not only the way films look but also how filmmakers tell their stories and how their characters speak and behave. When you watch the films of Quentin Tarantino, Gus Van Sant, Tim Burton, the Coen brothers, Jim Jarmusch, Jane Campion and Todd Haynes, you are seeing talented directors working with a sense of permission and stylistic nerve that David Lynch helped make possible. Lynch's first feature film, 1976's Eraserhead, was a spooky black-and-white independent venture that played like a sex nightmare captured in lucid form (well, semilucid). It told the story of Henry Spencer, a pillar-haired man who finds his already-fearful life made all the more fearful when he unwittingly fathers a demanding, helpless, half-human infant. Henry eventually kills the baby. Or maybe he just sets it free. Either way, the results are both awful and wondrous. The film's meanings were hardly plain (Lynch later admitted that the story partly reflected his own fears about the confinements of youthful marriage and fatherhood), but for many viewers, Eraserhead's fantastic imagery and industrial-Gothic atmosphere were meaning enough. Though some critics saw the influences of surrealism and expressionism in the movie, Lynch claims he was simply filming the vision that he saw in his own head. One thing is for certain: Eraserhead was a radical and indelible viewing experience, and it presented Lynch as one of the few fully original visionaries to emerge in postwar American cinema. Eraserhead played largely to college audiences and midnight art-house crowds. With his next film, The Elephant Man (produced by Mel Brooks), Lynch got the chance to reach for a broader audience. The Elephant Man was Lynch's version of the life of John Merrick, the horribly deformed man in Victorian England who briefly managed to transcend the cruelty of his own body and of the world around him. Lynch's script for the film was linear and fairly orthodox, even old-fashioned - like a 1930s or '40s misunderstood-beast horror tale - but the movie's cinematography had much the same abstract, spectral look as Eraserhead. The effort won Lynch an Academy Award nomination for Best Director and also earned him the chance to direct Dino De Laurentiis' production of Frank Herbert's epic science-fiction novel, Dune. The latter proved a disaster, an embarrassing, indecipherable mess - though, like nearly all of Lynch's work, it still held moments of stunning imagery. Lynch later forced the removal of his name from the film's credits. "With Dune," he says, "I felt like I had sort of sold myself out." Dune's failure turned out to be a saving grace. Had it been a mass success, Lynch might have got snared in the Hollywood machinery that reduces interesting film-makers to blockbuster formalists. Instead, with his next movie, Blue Velvet (1986), Lynch delivered a wonderfully twisted landmark of modern film. Blue Velvet is the story of Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan), a young man who returns to the small city he was raised in and finds that behind the town's pacific façades, people are living lives of malice, corruption and humiliation. Jeffrey also finds terrifying desires within himself, including an appetite for sexually abusing a woman (Dorothy, played by Isabella Rossellini) who is so damaged that, without more damage, she can no longer feel longing or trust. Blue Velvet - with its dark town and dark souls, and its strangely hopeful ending - earned Lynch his second Oscar nomination. Four years later, Lynch took the same obsessions that defined Blue Velvet and transported them to prime-time network television. Twin Peaks, an ABC series created by Lynch with screenwriter and author Mark Frost, was the story of a small-town homecoming queen, Laura Palmer (played by Sheryl Lee), whose murder tears open a whole community's intricate webwork of secret sex, violence and horror. It was also the story of FBI agent Dale Cooper (MacLachlan), whose investigation of Laura Palmer's death leads him to some creepy discoveries about how evil can share the places and dreams where people live, and how it can get passed along from troubled heart to troubled heart. For its first several weeks, Twin Peaks was a sensation. More important, it demonstrated that network television was capable of producing an audacious and cutting-edge work of culture. But Twin Peaks' ratings began to dip, and Lynch says the network pressed him and Frost to solve the central murder mystery. "The murder of Laura Palmer," Lynch says, "was the center of the story, the thing around which all the show's other elements revolved - like a sun in a little solar system. It was not supposed to get solved. The idea was for it to recede a bit into the background, and the foreground would be that week's show. But the mystery of the death of Laura Palmer would stay alive. And it's true: As soon as that was over, it was basically the end. There were a couple of moments later when a wind of that mystery - a wind from that other world - would come blowing back in, but it just wasn't the same, and it couldn't be the same. I loved Twin Peaks, but after that, it kind of drifted for me." After Twin Peaks, things misfired badly for Lynch. His prize-winning film at Cannes, Wild at Heart (based on the novel by Barry Gifford), seemed unfocused and loopy compared with his earlier, better works. Then Lynch made his worst mistake: He returned to the terrain of his greatest success, Twin Peaks, and plumbed its dark central story. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me aimed to reveal the events leading up to Laura Palmer's murder, but the TV series had already done so by outlining her descent into hell, then leaving its details to the viewer's imagination. Still, the movie had some powerful moments - a narcotized sex party at a roadhouse club, monstrous rages between Laura and her father, the bloody train-car murder ritual - and brilliant, terror-giving performances by Ray Wise (as Leland Palmer) and Sheryl Lee. Reviewers tore the film apart. This was not the Twin Peaks that fans remembered. Lynch's stellar moment had faded - or, some critics would say, had been tarnished by the director himself. He had changed film, he had changed television, but most of that was forgotten. Popular culture turns over quickly, and David Lynch had fallen off its wheel. WILL "LOST HIGHWAY" change that bad fortune? Hard to say. Certainly its unexpected plot turns and mystifying final movement may prove dismaying for viewers accustomed to the unambiguous narratives that define today's popular-film sensibility. "Every single element in a movie," says Lynch, "now has to be understood - and understood at the lowest common denominator. It's a real shame, because there are so many places that people could go if they weren't corralled so tightly with those kinds of restraints." Lost Highway, co-written by Lynch and Barry Gifford, is the story of Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a jazz saxophonist married to a dark-haired, sexy, cold woman named Renee (Patricia Arquette, in a tricky and award-worthy performance). Fred and Renee share a dark bedroom in a dark, almost windowless house (darkness is everywhere in the first part of this movie), but they don't share confidences, and they don't share time together. Fred suspects that Renee may have another life, another lover. One morning, Fred and Renee begin to find cryptic videos left at their front door, showing the two of them asleep in their bed. It's a scary intrusion, but for Fred it also represents another kind of violation: He hates the presence of a video camera. "I like to remember things my own way," he tells a policeman, "not necessarily the way they happened." One horrible night, Fred thinks he senses someone in the house. He wanders off into the house's blackness, and when he returns, Renee has been savagely murdered. Did Fred kill her? He isn't sure, but he ends up on death row for the crime. There, on another horrible night, he suffers a psychic implosion, and when he comes to, Fred no longer exists. He has been replaced by (or metamorphosed into) a younger man, Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), who possesses no memory of how he entered Fred's cell. Since Fred Madison and Pete Dayton are seemingly not the same man, and since the younger man is guilty of nothing more than an old car-theft charge, Pete is set free. He returns to his job as an auto mechanic, where one of his prize customers is a gangster, Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia), who has a taste for fine cars, ravishing women, guns and pornography. One afternoon, Mr. Eddy brings a Cadillac to the shop. He is accompanied by a lovely blond woman (also played by Arquette). That night, the blonde - who calls herself Alice - returns alone to see Pete, and the two begin a feverish affair. This, Mr. Eddy makes plain, is not to his liking. Alice grows frightened and wants to flee Los Angeles with Pete. First, though, she persuades him to help her rob a friend of Mr. Eddy's whom she sometimes fucks for money. The robbery goes wrong; Pete accidentally kills the man (horrifically but also hilariously). It is then that Pete finds out Alice is not the woman he thought she was and that everything in Lost Highway - time, fate, identity and love - turns inside out. There's more that could be said about the film's plot twists and characters - especially about a gnomish figure called the Mystery Man (played with elegant menace by Robert Blake), who reckons crucially into Fred's and Pete's fates. But a narrative exposition can't truly illuminate what Lynch has accomplished with Lost Highway. Long after the movie's frantic closing moments, you will wonder how its mysteries fold in on one another. Who killed Renee? Are Renee and Alice the same woman? And the Mystery Man: Just who the fuck is he? Is he an incubus or a demon - or is he as close to an honest and redeeming character as can be found in this story? The keys are all there - Lost Highway is not simply an absurd conundrum - but the answers can be as hard to uncover as the hidden details of a dream. "You can say that a lot of Lost Highway is internal," says Lynch. "It's Fred's story. It's not a dream: It's realistic, though according to Fred's logic. But I don't want to say too much. The reason is: I love mysteries. To fall into a mystery and its danger ... everything becomes so intense in those moments. When most mysteries are solved, I feel tremendously let down. So I want things to feel solved up to a point, but there's got to be a certain percentage left over to keep the dream going. It's like at the end of Chinatown: The guy says, 'Forget it, Jake, it's Chinatown.' You understand it, but you don't understand it, and it keeps that mystery alive. That's the most beautiful thing." Barry Gifford, Lynch's co-writer on Lost Highway, is slightly more forth-coming. "Let's say you don't want to be yourself anymore," he says. "Something happens to you, and you just show up in Seattle, living under the name Joe Smith, with a whole different reality. It means that you're trying to escape something, and that's basically what Fred Madison does. He gets into a fugue state, which in this case means that he can't go anywhere - he's in a prison cell, so it's happening internally, within his own mind. But things don't work out any better in the fugue state than they do in real life. He can't control the woman any more than he could in real life. You might say this is an explanation for what happens. However, this is not a complete explanation for the film. Things happen in this film that are not - and should not be - easily explained." Gifford is right: There's more to Lost Highway than its mysteries. There's also the movie's painterly photography, the tense and subtle performances by Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette, and the bravura creepiness of Robert Blake's Mystery Man, plus a throbbing undercurrent of ambient sound by Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor during the video sequences. All these elements add up to making Lost Highway a film about the wonder of what film can be. "For me," says Lynch, "a film exists somewhere before you do it. It's sitting in some abstract world, complete, and you're just listening to it talk to you, telling you the way it's supposed to be. But not until all the sound and music and editing has been done do you truly know what it is. Then it's finished. It feels right, the way it's supposed to be, or as right as it can. And when it's finished, you're back in a world where you don't control anything. You just do the best you can, then say farewell." IN THE DAYS BETWEEN MY FIRST and second conversations with David Lynch, actor Jack Nance - whom Lynch had worked with for 25 years - was found dead in his South Pasadena, Calif., home. The day before, Nance had gotten into a fight with two men in a doughnut shop and suffered a severe head blow. It was Nance who played Henry, Lynch's high-strung alter ego in Eraserhead. He also appeared in most of Lynch's subsequent films and played the part of Pete Martell, the long-suffering lumber-mill foreman, in Twin Peaks. In that series' opening moments, he makes the awful discovery of Laura Palmer's dead body; in its final hour, he is blown to kingdom come. "He was one of my best friends," says Lynch. "Jack had a quality . . . it's hard to put into words, but in my mind, Jack was a real Kafka character, Gregor Samsa [the man transformed into a cockroach in The Metamorphosis], which means to me: He understands trouble. He's trying to do the right thing, but he's also sensing the darkness and confusion of the world. That was pretty much Jack. He really had a pretty rough life, and it was rougher because he was a thinking person. Sometimes when you don't worry so much about stuff, you're actually kinder to yourself." Nance's death bears close relation to Lynch's work. Clearly, this is a dangerous world - death and destruction are often closer than we would like to believe - and this is one of the major themes of Lynch's movies. But it is also Lynch's powerful treatment of this theme - especially the way he presents the caprices of violence - that has turned many critics against him. Some reviewers found Wild at Heart's impassioned scenes of brain bashing and decapitation all but unbearable, and Fire Walk With Me was excoriated for its depictions of father-daughter incest and murder (which, actually, were quite heart-rending). Other critics have expressed outrage at Lynch's portrayal of female characters as either victims or malicious seductresses (particularly Dorothy in Blue Velvet). Lost Highway likely won't be immune to these protests. In the preview screenings I saw, several viewers audibly gagged at the scene where Alice's slimy fuck-for-money customer is killed (I think it's the sound effect, which is astonishing). More troubling is the scene where Alice is forced to strip at gunpoint for Mr. Eddy. She is terrified at first, but her body starts to undulate in movements of pleasure, as if she's turned on by being forced into this act. Then she puts her head between Mr. Eddy's legs, smiling the perfect smile. These are moments that will drive some viewers nuts - particularly those who think that depictions of explicit violence and chancy sex threaten the moral or cultural sanity of our times. Lynch has been hearing these arguments for years. "I'm not sure what these people are saying," he says. "Is it that if you depicted no graphic violence, the world would calm down and there would be less violence? Or is it that if you sense certain things about violence and then portray those things in a film, does that make the violence go to another level? Or is the violence in films a way to experience something without having to do it in real life? "It's a tricky thing," he continues. "When you're an artist, you pick up on certain things that are in the air. You just feel it. It's not like you're sitting down, thinking, 'What can I do to really mess things up?' You're getting ideas, and then the ideas feed into a story, and the story takes shape. And if you're honest about it and you're thinking about characters and what they do, you now see that your ideas are about trouble. You're feeling more depth, and you're describing something that is going on in some way. "In film, life-and-death struggles make you sit up, lean forward a little bit. They amplify things happening, in smaller ways, in all of us. These things show up in relationships. They show up in struggles and bring them to a critical point. "I don't know where to break this thing," he says. "Are we in the business of falling in love with stories? What if every movie had to have a positive message at the end? If we only put out pleasant films, nothing would really stop, except that people would stop going to the movies." IN SOME OF HIS EARLIER WORK, David Lynch would deliver something magnificent and terrible only to creep back from its implications. At the end of Blue Velvet, after a night of mayhem and death, pretty birds come out to sing (though they hold worms in their beaks). In Twin Peaks, after Leland Palmer confesses to killing his own child, we learn that he had actually been occupied by an otherworldly presence - something that FBI Agent Dale Cooper found more comforting than the idea that "a man would rape and murder his own daughter." In these moments, some semblance of order is restored after all the horror. "Once you're exposed to fearful things . . ." he once told ROLLING STONE, "you begin to worry that the peaceful, happy life could vanish or be threatened." In Lost Highway, Lynch does not pull back. The plot delivers you to no easy place. Order is not restored, and not all the guilty are clearly punished. (After all, who isn't guilty in this story?) Instead, the movie's final moments are nothing but chaos and fear. This may sound strange, but there is something heartening about witnessing one of America's most inventive artists allowing his art to grow darker, more difficult - especially at a point where he has everything to lose and at a time when there are loud voices in our culture who can stand no more admissions of darkness into the popular arts. Lynch has decided to put his vision up on the screen and protect neither himself nor us from it. Maybe he's saying that life's fractures aren't always easily comprehended or corrected. Or maybe he's saying that art shouldn't be reduced to something that, in the end, serves mainly to allay our anxieties or reinforce a fiction of order. Either way, it's a hell of a treat to see a brave artist working again at full strength. There's something about it that, truly, thrills the soul. Trent Reznor Makes a Case for Danger SOME OF THE MOST WONDROUS MOMENTS in David Lynch's Lost Highway owe significantly to the aural genius of Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor. His thick, ambient drones - during the film's mysterious video sequences - give the fated house where the film's two main characters, Fred and Renee, live a life all its own; it's as if the walls were breathing and murmuring, or trying to whisper horrid secrets. In his own way, Reznor has created a tense and powerful soundscape here that is as inventive (and likely to be as style defining) as Bernard Herrmann's orchestration for the famous shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho. Like Lynch, Reznor is one of the artists who is helping to change popular culture's mainstream sensibility. His 1994 album, The Downward Spiral, is among the most radical sound assemblies ever to become a multi-million seller, and also one of the most ingenious: It mixes violent textures with lovely melodies, all to frame a harrowing, deeply affecting story of one man's descent into his own abject soul. The effort made Reznor a major star - and a busy one. In the years since, he has toured with Nine Inch Nails, supported David Bowie on another big tour, produced the startling soundtrack for Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers and also helped produce three CDs for shock-rock fave Marilyn Manson, including Antichrist Superstar. Reznor also became a target for cultural moralists William Bennett and C. DeLores Tucker, who expressed outrage at what they viewed as his music's assault on decency. What Bennett and Tucker fail to comprehend is that there's more than one mainstream in America. There's also a mainstream in which people acknowledge and cope with pain and fear and anger. It's not a small one; if it were, there wouldn't be so much disturbing or so-called dangerous art that is also so popular. Reznor is a star not just because he makes great sounds or looks sexy; he's also a star because his audience likes and needs to hear what he has to say. His new songs on the Lost Highway soundtrack (which also includes new music by the Smashing Pumpkins, Marilyn Manson, Lou Reed and David Bowie, among others) are the only things we'll be hearing from Reznor for a while. He's working simultaneously on two new records, but he isn't willing to say when they'll be released. I interviewed him twice - once in his Los Angeles hotel room and a second time during a late-night phone conversation. I found him to be a gentle-mannered, soft-spoken and steadily thoughtful man who isn't afraid to say strong things. How did you come to work with David Lynch? What was your estimation of the film? There's no really easy closure in the movie. It's more like a Mobius-strip story than a beginning-to-end narrative. That may prove difficult for some viewers. . . . I think that with that series, he was tapping into a consciousness of America that America wasn't quite ready to accept from its mass entertainment. Years ago, Lynch told "Rolling Stone" that part of what he was trying to do with his films was "to make art popular." Does that in any way describe what you are trying to do with your music? But because your work does well on the charts, doesn't that also make your music, in a sense, mainstream? Why is that? Well, there's a flip side to that. Because a lot of people like your music and seem to identify with what you're saying, some writers have said that - just like Kurt Cobain a few years ago or Bob Dylan a generation ago - you are now speaking to and for a certain generation and its sensibility or experience. Are you comfortable with that description? But you have also been criticized for being a bad influence on your audience. Your song "Big Man With a Gun" was cited by William Bennett and C. DeLores Tucker as being dangerous because of its violent imagery. Your music and that of Tupac Shakur and the Death Row gangsta-rap artists were a large part of why Bennett and Tucker demanded that Time Warner disavow its relationship with Interscope Records. Do you ever worry that some music could have a damaging influence on an audience? I remember, for example, Lou Reed once telling me that he'd stopped performing "Heroin" for a time because too many people told him that song had inspired them to shoot junk. In a way, that brings us back to the subject of the mainstream. Some of these same moralist critics say that what's bad about music like yours is that it assaults or offends mainstream values. But a lot of people would say that art - whether it be music, film or any other form - has an obligation to improve the world. Do you think art has any obligations? What about the art that addresses people who might want to kill somebody other than themselves? You've talked a lot in the past - and on "Downward Spiral" - about self-loathing. Would you say that you now like yourself better than you did before? What will the new music be like?

He was looking for somebody to provide some of the sound for Lost Highway, and a friend suggested he give me a call. I hadn't seen the film, but I'm a huge David Lynch fan - we used to hold up Nine Inch Nails shows just so we could watch the latest Twin Peaks. So we set up a weekend for him to come to my place in New Orleans. At first it was like the most high-pressure situation ever. It was literally one minute, "Hi, I'm David Lynch," and he's cooler than I even imagined he would be. Three minutes later, he's saying: "Well, let's go in the studio and get started." Then he'd describe a scene and say, "Here's what I want. Now, there's a police car chasing Fred down the highway, and I want you to picture this: There's a box, OK? And in this box there's snakes coming out; snakes whizzing past your face. So, what I want is the sound of that - the snakes whizzing out of the box - but it's got to be like impending doom." And he hadn't brought any footage with him. He says, "OK, OK, go ahead. Give me that sound."

He wasn't doing it to intimidate me. At the same time, I had to tell him, "David, I'm not a film-effects guy, I don't have ad clients, and I'm not used to being in this environment. I don't work that way, so respect that and understand that I just need a few moments to be alone, so that I know that when I suck, no one is knowing I'm sucking, and then I'll give you the good stuff." I'm thinking, "Boy, he must think I really suck now." But by the end it went cool. And then he turned over all the music that was in the film and asked me to make a CD out of it. So I've done my best to make the CD a fair representation of the film, because this isn't Mortal Kombat, you know. This is David's movie. To the person who hates pop music who buys this David Lynch soundtrack, they will get what they want out of it. At the same time, I want it to have some degree of accessibility for the 13-, 14-year-old kid who buys it because I have a new song on it; or for the Smashing Pumpkins fan who buys it for that. Anyway, I think the whole thing flows, and that's my main contribution to that project.

When I saw the finished one, I thought, "Fuck, this is fantastic." It's abstract and bizarre, but it also has enough payoff. But there is that one weird night in the movie [when Fred transforms into Pete Dayton]. I wanted to know what the fuck happened that night.

But that's another reason to praise [Lynch], in the sense that he's not really catering to them. You get it or you don't. When I saw Blue Velvet, I walked out of the theater changed and very shaken. I talked to someone later, and they said, "Didn't you think that was funny?" I didn't think it was funny. I was terrified because, when I saw it, I realized I would have done exactly the same thing as Kyle MacLachlan's character. I would've tried to sneak in, I would've felt for her - I would've done it all.

I also remember the Twin Peaks episode where Leland bashes Maddie's head against the wall, and then he's driving his car with the body in the back. I thought, "This is the scariest, most violent thing I've ever seen on television, ever. Fuckin'-A, someone got away with it." I could also see why people had a problem with it. It wasn't, you know, Fresh Prince of Bel Air.

That reminds me of something David said to me one night. We drove past some billboard of some soon-to-be-playing movie. And he says, "You know, I kind of envy, in a way, someone like Steven Spielberg, who I think really does what they believe in 100 percent, and it just happens to jibe with the consciousness of America and its billion dollar-making movies. I don't think he's catering to the market so much as he's doing what he really believes in. I do what I believe in, which is all I can do, and it gets a slice of whatever." It struck me as an interesting way to look at things. I could see where, as a director, you could be bitter about the guys who have that success, but that isn't him. It impressed me, that sincerity, almost a naiveté.

Sometimes in my music, I'll try things, and I'll think, "No one's going to like this, but it's not fucking Bush." I'm not claiming it's the weirdest avant-garde contemporary piece ever, but hopefully it challenges you. Either you don't like it, or you think, "Fuck, that's cool - that makes me realize how shitty the stuff is that I've been listening to." I'm stretching it a bit here, patting myself on the back.

Well, it sounds pretentious to say that, but, yeah, I do look at it as art, not just as selling records or making a commercial product. I'd like to open people's eyes up to something a little bit different than the mainstream crap that's out there. I think I took a lot of the things I liked and kind of recycled and hopefully added something to them - maybe that hook that they didn't have before - and maybe that might reel in a listener who wasn't as in tune with that sort of sound. Maybe it opens their eyes to a new thing. That's the aspiration, anyway.

If you'd asked me years ago, when I started, I'd have said, "No, I'm not mainstream." But that's a blanket of protection you wear to avoid saying something that could be perceived negatively. Yeah, I think my music is mainstream. You can't sell that many records and still think that you're in the underground. I'm not saying you can't have that underground or alternative element to it, but the underground has infiltrated, to some degree, into the mainstream. But the reason I sleep well at night is because I know I didn't try to cater to the mainstream. Before The Downward Spiral came out, I said to the label, "Look - sorry, but I don't think there's a fucking single in here. I don't think it's going to sell for shit, but I had to make this record, because it's what I'm about right now; I believe in it 100 percent. I'm sorry, though, there's not something to justify the money you gave me to make it." Then "Closer" takes off, and the fucking record sells 2 or 3 million copies. It surprised me because - not to sound lofty, but I didn't think people would get it, you know?

Well, I made the first song on the record, "Mr. Self Destruct," sound like I wanted it to be: the shittiest sounding thing that, by the end, just deteriorates into noise. It is not fucking Michael Jackson. Then I followed it with a light, swinging jazz song - just the exact opposite of what you'd expect. And then with "Closer." ... I wrote that song, and I was afraid to put it on the record. I thought I could make a whole album of noise with me screaming, and I'd be safe, at least with the people who liked Pretty Hate Machine. But instead, "Closer" is a song with a simple disco beat and a Prince kind of harmony vocal line. That, I thought, would open me up to a lot more criticism from the safe company of alternative people I'm supposed to be catering to. Then, when The Downward Spiral took off, I thought, "Fuck, this is what I want to do." It should be like that, you know?

The new stuff I'm working on is even more disparate than The Downward Spiral. I'm not afraid of trying things out. This next record: It will either be huge or a career stopper. It won't be safe, that's all.

I went through a phase where I thought we [Nine Inch Nails] were the cool thing that only a few people or critics knew about. And then our records started infiltrating suburban malls. And then little kid sisters started wearing Nine Inch Nails shirts. And then, suddenly, it's not as cool as it was before, even though it's the same music. And I had this knee-jerk reaction: "Fuck you, and now I'm more pissed off, so I'll make something even more unlistenable." But I wasn't being true to myself then. I was catering to an audience that I was trying to re-prove my credibility to. And some of those people are full of shit in the first place.

Let me tell you a story about something that really helped me out: I saw U2 for the first time, on their Zoo TV Tour. I was backstage with Marilyn Manson, sitting in a room, and Bono comes in. I'd never met him, but we knew of each other through Flood, the producer who worked on both our records. Bono sat down and talked with me for an hour, and we had this kind of drunken mind meld. I said: "I'll tell you what I'm going through now. We went from being underground-elite darlings to the point where we're getting shit on by those same people because now we sell records. And I know you guys have gone through the same thing." Bono says: "Fuck those people. That's like saying, `You're cool enough to listen to my music, but you - you grew up in Wisconsin; you're not cool enough to listen to it.' That's a kind of fascism." He goes, "You do what you believe you have to do. That's what we've always done. You believe in yourself and don't worry about the people who don't like it because it's not the right fashion statement that they're trying to adhere to."

Now U2's not my favorite band, but I do respect them, and in the same way I respect Bowie: They change without fear of change. I left that night thinking, "He's right. Why am I concerned about some snotty-nosed college magazine that thinks I'm not cool because people liked the record and bought it?" After that, I got over that whole thing.

It's an unwelcome statement because I don't consider myself that at all. I never have. I think that maybe what I'm saying, people of that generation picked up on and related to, but by no means do I think that.... Look, I just sat in my bedroom and wrote how I felt, why I was upset about things, filled up a piece of paper and sang it, and then people related to it. That's as far as it goes. There isn't anything lofty about it.

They don't have any idea what they're talking about. They called Nine Inch Nails a rap band. I think my music's more disturbing than Tupac's - or at least I thought some of the themes of The Downward Spiral were more disturbing on a deeper level - you know, issues about suicide and hating yourself and God and people and everything else. But I know that's not why they singled me out. They singled me out because I said fuck in a song, and said, "I got a big gun and a big dick."

That song's a piece of art, though. The first and only time I ever tried heroin, I listened to that song. I was in a big Lou Reed phase, and heroin seemed like this whole glamorous .. . thing. Then I realized, "Hey, this is shitty." It wasn't really the song - it was my own decision and my own stupidity. You could say that song is dangerous, but it should be. If nothing else, it brings the subject to light, you know.

I did a song on Downward Spiral where I'm talking about killing myself. I dreamed it, and I thought it, and it was like, "Oh, God, I'm going to do this." So I wrote it into a poem, and I found it tied in with the theory of the record: that at the worst state the character goes into, suicide might be an option. But I think by just saying it and bringing it to light, maybe it helps. I've been so depressed about things, and then I'll hear a song, and I'll think, "Fuck, I can relate to that. Someone else feels that way." In its own way it becomes enlightening, and I feel release. When I'm onstage singing - screaming this primal scream - I look at the audience, and everyone else is screaming the lyrics back at me. Even though what I'm saying appears negative, the release of it becomes a positive kind of experience, I think, and provides some catharsis to other people.

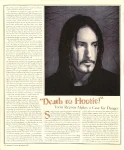

When I was growing up, rock & roll helped give me my sense of identity, but I had to search for it. I remember I loved the Clash, but I was an outcast because you were supposed to like Journey. Before that, I loved Kiss. The thing these bands gave me was invaluable - that whole spirit of rebellion. Rock & roll should be about rebellion. It should piss your parents off, and it should offer some element of taboo. It should be dangerous, you know? But I'm not sure it really is dangerous anymore. Now, thanks to MTV and radio, rock & roll gets pumped into your house every second of every day. Being a rock & roll star has become as legitimate a career option as being an astronaut or a policeman or a fireman. That's why I applaud - even helped create - bands like Marilyn Manson. The shock-rock value. I think it's necessary. Death to Hootie and the Blowfish, you know? It's safe. It's legitimate.

Look at Marilyn Manson: They have no qualms about taking that whole thing on. The scene needs that, you know? It doesn't need another Pearl Jam-rip-off band. It doesn't need the politically correct R.E.M.s telling us, "We don't eat meat." Fuck you to all that. We need someone who wants to say, "You know what? I jack off 10 times a night, and I fuck groupies." It's not considered safe to say that now, but rock shouldn't be safe. I'm not saying I adhere whole-heartedly to all that in my own lifestyle, but I think that's the aesthetic we need right now. There needs to be some element of anarchy or something that dares to be different.

I do in the sense that I think it might help somebody understand themselves better. It's like what we were talking about before. I write a song about killing myself. You hear it, and you go, "I'm not the only person who ever felt that way." You feel safer in knowing you're not the only person who ever thought that. And I think: "Mission accomplished." To me, that's the way art communicates to people, that's how it helps.

There's a part of me that is intrigued by that. For example, I loved the Hannibal Lecter character in The Silence of the Lambs. The last person I want to see get hurt in that story is him. And I think, "Why do I look at him as a hero figure?" Because you respect him. Because he represents everything you wish you could be in a lawless, moral-less society. I allow myself to think, "Yeah, if I could kill people without reprimand, maybe I would, you know?" I hate myself for thinking that, but there's an appeal to the idea, because it is a true freedom. Is it wrong? Yeah. But is there an appeal to that? Yeah. It's the ultimate taboo.

My awakening about all that stuff came from meeting Sharon Tate's sister. While I was working on Downward Spiral, I was living in the house where Sharon Tate was killed. Then one day I met her sister. It was a random thing, just a brief encounter. And she said: "Are you exploiting my sister's death by living in her house?" For the first time the whole thing kind of slapped me in the face. I said, "No, it's just sort of my own interest in American folklore. I'm in this place where a weird part of history occurred." I guess it never really struck me before, but it did then. She lost her sister from a senseless, ignorant situation that I don't want to support. When she was talking to me, I realized for the first time, "What if it was my sister?" I thought, "Fuck Charlie Manson." I don't want to be looked at as a guy who supports serial-killer bullshit.

I went home and cried that night. It made me see there's another side to things, you know? It's one thing to go around with your dick swinging in the wind, acting like it doesn't matter. But when you understand the repercussions that are felt ... that's what sobered me up: realizing that what balances out the appeal of the lawlessness and the lack of morality and that whole thing is the other end of it, the victims who don't deserve that.

I've got more thanks and praise and more money than before. But from a self-esteem perspective, I've liked myself more.... I've lost friends. I've lost band members. I've lost a sense of self-worth in a way. And while I always wished I'd get to this place of success, once you get it, it's not that great. I'm not bitching about it. I mean, it is great in a million ways, but it's not self-affirming on every level, and you wish it was. I don't go to sleep thinking, "I'm Kevin Costner," you know, "I've done it!"

And the bigger you get in the rock arena, the more people want to fuck with you, to tear you down and criticize you. For example, you write a song that you think is dangerous to write because it says something that you're embarrassed to say. But because it's embarrassing, because it's extreme in its nature, then you've got everyone saying, "He doesn't mean it. He's just trying to cash in." You find yourself initially saying, "Yes, I did. I meant it. I am that bummed out."

I would only hope that maybe, in a world of insincere, bullshit, pop-music crap, this music might make a difference. And that's why I do it: I think it does. But at the same time, think how much easier it would be to be a bland rock band that doesn't mean anything and just make money.

There will be two records that will probably come out around the same time. One will be with people I had with me in the live band. We're playing and writing together in a group called Tapeworm. That one will be a bit more like what you think industrial music is like now. The new Nine Inch Nails will be more like a funk hip-hop record. It will piss a lot of people off, and it's going to change the world at the same time, I hope. That's all I can aspire to. That and staying 10 steps ahead of Billy Corgan.